Exclusive Interviews

Peter Levy - SMB Archive Interview: 08/01/2011 by Ryan Hoss

You won't notice Peter Levy's name listed in the credits for Super Mario Bros. as the director of photography--you'll see Dean Semler. The reason for this is that Levy left the project a few weeks after filming. For the first time, we get the story straight from Levy himself. He was involved with many of the scenes you'll see in the opening of the film, and also shot many scenes that didn't make it into the film. --Ryan Hoss

RH: Peter, I really appreciate you agreeing to talk with us today.

PL: Well, yeah. I’m more than happy to. All I can say, Ryan, is that it was 16, 17 years ago. My memory might be pretty hazy, so feel free to ask me anything. It may prompt my memory.

RH: So, first of all, could you tell us a little about yourself and how you got into cinematography and how you initially came onto the Super Mario Bros. project?

PL: Well, I started off when I was 19 years old. I did the stills on an independent Australian film. It was the first time I had seen a cinematographer in action and I was just completely overwhelmed and enamored by what I saw. I just knew deep down without any doubt that that’s what I wanted to do.

So, I became an assistant and worked on documentaries and then started shooting documentaries and music videos and TV miniseries and commercials and then finally features. I moved to America in about 1989. I came to do Nightmare on Elm Street V, and followed that with Predator II. It was a busy time because between pictures I was doing commercials and I was working with Rocky and Annabel for their commercial company and I did about half a dozen commercials with them. They told me they had this picture coming up and they asked me to do it. And that was it. I agreed. I did have reservations about their ability to handle the discipline of shooting a feature film but I guess the fact that Roland Joffé was producing made me feel a little safer, if you like.

"I just knew deep down without any doubt that [cinematography was] what I wanted to do."

RH: So, you came on with Rocky and Annabel. I’m not sure how much you know about the production beforehand, but Roland was on it from the beginning. For a long time they were almost going to shoot a completely different movie that would have been a fantasy version of Mario Bros. They had a different script and director and everything. That whole version was scrapped and then they brought Rocky and Annabel in.

PL: No. I didn’t know about the other version. I knew that Roland was basically looking for a cash cow for his company - something that would finance his independent films and create some cash flow. I honestly don’t think Roland had much heart in this project per se – it felt like he was doing it more as a business commitment. I always got the feeling that he would rather not have been there.

RH: That’s an interesting point to kind of analyze because I believe Super Mario Bros. was the first film that Roland produced after directing all of his other films. This was his first film where he took a producer’s role.

PL: Yeah. And my feeling at the time was--and still is--I think Roland was showing Rocky and Annabel almost too much respect. He was showing them the respect that he would want as a director, but Roland’s track record and experience was a lot different to theirs and I think that he should have been able to see that the directors were making very bad decisions and step in and, at least, advise them otherwise. Not that Rocky and Annabelle would have listened – they were quite the contrarians, they tended to take the opposite stance on whatever advice or suggestions they were given.

RH: Right. We’ve heard lots of stories. It was only Rocky and Annabel's second big feature.

PL: It was their first. All they’d really done was Max Headroom. Oh sorry. I beg your pardon; they did D.O.A., didn’t they?

RH: Yes, they did D.O.A. first in 1988, I think.

PL: Well, they made a bit of a mess of Mario Bros. I guess they just weren’t used to the discipline of feature-film shooting; that is, amongst other things, a commitment to the narrative over the visuals. Substance over style, if you like.

RH: Right. We’ve heard that from a couple people. They seemed to want to do things their own way even though they were surrounded by more experienced people. They still kind of wanted to do things how they wanted to do them. And like you said, I guess the film kind of didn’t work in some places.

PL: It made it very hard. It made the day’s schedule very hard to make. The directors are also responsible for making sure they get the day’s work done in day. The director can either waste or save their own day. They would do re-take after re-take for some minor detail of art direction, which, I could see was driving the cast crazy. I think that they felt that it was their style and quirkiness that got them this far already, so why change.

RH: How long were you on the project?

PL: I remember that it was a fairly long time of prep and a couple of weeks before they replaced me. So, probably a couple of months.

RH: What kinds of things did you shoot? Were they mainly the New York/Brooklyn scenes or did you get to shoot inside the cement factory in the alternate world? Did you do both or just one or the other?

PL: I prepped the cement factory. We were getting sets ready. I think, from memory, I think we were out on location doing most of the location-work to buy more time to get the sets built and because there was a lot of stuff evolving that hadn’t been made or decided upon by the time we started shooting, so we obviously couldn’t shoot those scenes. So, from memory, I think most of my stuff is in the early part of the film – the location work.

RH: Have you seen the finished film?

PL: Years and years and years ago. Yeah.

RH: Years ago? What did you think of the film overall when you first saw it after having left the project?

PL: God. From memory, I felt I think it was trying to be too sophisticated for its audience. Rocky and Annabel were trying to impress people of their own generation of colleagues and not the target audience. And I felt that some of the animation was a bit of a cop-out.

RH: I think that is kind of what happened. The one big fault of the film is that there just isn’t a consistent tone. It’s a love story and a comedy, yet there’s also a lot of action and adventure. It’s for kids with a lot of the cute little gags, but it’s also for adults with the sexual undertones.

The tone itself is dark and scary, yet it’s also funny. It doesn’t settle on one thing. It was something that tried to be for everybody but ended up alienating a lot of the target audience.

PL: I think they just tried to milk each scene for what it was worth, like a commercial, and they lost the vision of the overall story.

RH: And I think the vision and concept behind the film is so strong. It’s sad to see that it wasn’t as successful as it could have been.

PL: Yes. Interestingly enough, if it were made with the powerful CGI tools we now have the results would be a lot different. Probably a lot better. We were sort of hampered by the fact that everything we had to shoot had to physically exist and be photographed.

RH: Right. We’ve been able to talk with Chris Woods, the visual effects supervisor, and he had all kinds of interesting stuff to say because the movie has this really interesting clash between early, but very sophisticated for the time computer effects combined with practical work. It was just this very interesting mish-mash between the two.

PL: Yeah. It was fledgling days of those techniques. We were stumbling our way through. I don’t just mean on that film, but in the early days of CG.

"We were stumbling our way through. I don’t just mean on that film, but in the early days of CG."

RH: Right. So, one of the interesting things that I’ve been wanting to talk to you about in particular is that we’ve heard that a lot of things changed, especially in early parts of the film. It seems like there are a lot of either alternate scenes or just scenes that were just completely cut out. I was wondering if you could remember any of those and what they were and if there’s anything significant that you shot that is not in the final film. (pause) I can try to jog your memory. (laughs)

PL: Yeah, try to jog my memory. (laughs)

RH: Well, there’s an introduction where the Mario Bros. are fixing a dishwasher in a café and they encounter two rival plumbers, the Scapellis, and they lose that job. To make up for it, the restaurant’s owner offers them a free meal. I think that’s initially where Mario and Luigi meet Daisy, inside the restaurant, but that scene was taken out and rewritten so that they instead meet her on the street corner.

PL: I remember that scene but I can’t help you with much else.

RH: That’s the major thing. I think there’s some other scenes set in their apartment where Mario and Luigi are either getting ready for their date or talking about “family pride” and what it means to be a “Mario.”

PL: Yeah it does, vaguely. Again, I don’t remember anything in particular of shooting it or what was around it. Yes, I do remember there were lots of script changes. Dramatic script changes were coming in all the time, last-minute stuff. But that’s not unique to Mario Bros.

It’s not uncommon for rewrites to be coming down on the day you’re shooting it, but I do remember on that film there were a lot.

RH: A lot of people think that the movie is kind of slow in those parts but, again, it’s the issue of what the intended audience wants to see. I thought those parts were really good and I thought that it should have been more because the first act of the movie is pretty much the only time that you have to establish the characters before you have to go into the alternate world. Once they’re there and you’re in the second act you have to explain that world and what’s going on there.

PL: Yeah. That’s true.

RH: What’s interesting is that Rocky and Annabel came from an animation background and they tried to do new and different things with commercials and computer graphics, but I guess after Mario they decided to go with a different direction.

PL: I’ve got to say it was really exciting working with them on commercials. They had and still have a feel for that format. I remember the commercial-work we did was exciting and good strong, daring work. But there’s certainly much more than a strong visual style and a sense of what’s hip required to succeed at feature filmmaking and storytelling.

RH: Right. Right. I guess more things need to be set in stone early on. Things that shouldn’t be changed or that just shouldn’t attempted to be changed. We’ve spoken to one of the screenwriters, Parker Bennett, and a lot of what he said is that they had lots of great ideas, but they would change too many things. They would agree on something one day, but then Rocky and Annabel would want to do something completely different the next day even if that meant setting the production back.

PL: I do remember them wasting a lot of production time with last minute changes. It was exasperating for those around them who were trying to help them. They were their own worst enemies – they wouldn’t be helped. They were suspicious or disdainful to everybody. The goodwill from the crew ran out very quickly.

I think for Rocky and Annabel the whole shooting thing is an evolving process. We start with a lot and then we’ll just keep whittling down and we’ll get down to what we think we really want. We’ll work it out when we see it, which is a technique you can do in commercials but it’s just not viable for feature or dramatic shooting.

RH: It becomes different when you have a film that has a story that you need to tell. If you tell too many things you lose some focus.

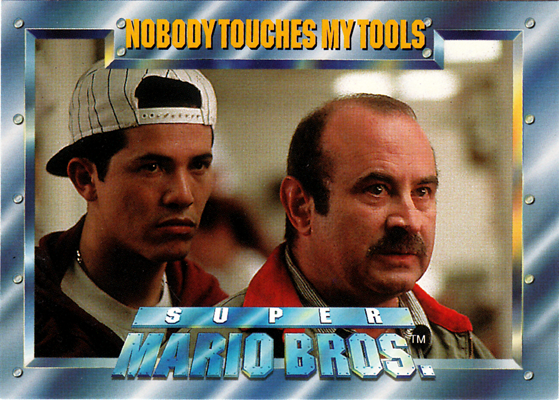

PL: Yeah. I can give you one example. I remember shooting the scene in the kitchen. There’s bus boys walking behind them carrying big, big plates of dirty dishes into the kitchen. So we do the scene and Rocky says “I want to do another one, but I want to see more spaghetti coming off the bus boys’ plate.” I remember I caught Bob Hoskins’ eye and we rolled eyes and then we shot that one with the new, improved spaghetti and then Bob Hoskins [says] “Okay, I want to do another f*cking one because my eyebrows aren’t right.” (laughs)

“Okay, I want to do another f*cking one because my eyebrows aren’t right.”

RH: (laughs) I guess that would rub actors the wrong way when they’re more concerned about the visuals than the performance.

PL: Yeah, especially those style of actors. John Leguizamo was a lot more flexible in those days because he was just a young up-and-comer and he didn’t have as much experience or reputation to protect, but no actor wants to be made to come off foolish.

RH: Right. And that was a fantastic cast to work with. They were incredibly talented actors.

PL: Yeah, a really good bunch, it turned out.

RH: Do you have any other stories like that? Shooting scenes or anything like that?

PL: (sighs) Not that I can think of. I don’t want to put Rocky in a bad light. But yeah. That was sort of the tone from my perspective - that distractions and minutiae became of paramount importance and no one was thinking about the big picture. I was under a lot of pressure from the producers to get the day’s work done on time. Roland would come up to me and whisper “….you should make them shoot it this way, not that…” or “…tell them that they don’t need that shot…” I remember being rather pissed at him for that – because that was his job to control his directors, not mine.

RH: Right. I’m trying to think of the early parts of the film. Did you happen to shoot the scene early, early on with Daisy’s mother being chased by Koopa in the rain or in the abandoned mine shaft or inside the church with the nun and the egg?

PL: I think my work is probably in the first 10 minutes of [the film]. (pause) Yeah, I’m trying to think… Did I get into the cement factory? Yeah, we started working in the cement factory because I know I shot there. I spent months prepping the damn place. I know we shot there. I know I shot some scenes. (pause) Is that cement factory still standing down there?

RH: Yeah, it’s still there. The last I heard is some company wanted to buy it out and retool it for some other purpose. But yeah, it’s still there. I think they shot some other movies there, but I’m not sure what’s there at the moment.

PL: Yeah. In those days there was talk to buy it and make a film complex around it. I do remember there was an assistant prop man who, poor guy, had been the prop man and armorer on--was it The Crow that Brandon Lee [was in]? He was the guy that supplied the gun that killed Brandon Lee.

RH: Oh. Oh yeah…

PL: That was unfortunate.

RH: Yeah… (pause) So, that’s interesting--you had worked with Rocky and Annabel on commercials and they wanted to bring you in because you had worked with them before?

PL: Exactly. They knew I’d shot a lot of large feature films so I was familiar with the procedures and techniques of a large production and we had built up a good rapport working on commercials over the previous year. I think that I showed them that I was willing to be risky and try new things, so that, combined with my feature experience seemed like a good fit.

RH: Did you work with them on Max Headroom or was that somebody else?

PL: No, no.

RH: Oh, okay. Because it seems like there was a lot of similarities between the production Max Headroom and Super Mario Bros. in terms of trying to get a story that worked and figuring out how to make it work. I think both were shot in an abandoned type of facility. I think Max Headroom was shot in abandoned gasworks or something. So it’s really interesting that the two had a lot of parallels and a lot of the same problems.

PL: Yeah. I guess animation is a lot more flexible. There’s not as many people involved when you change your mind.

RH: Yeah. Could you talk a little about when you left the project and how that went?

PL: Well, I remember Roland sacking me and basically saying it wasn’t me. They needed a sacrificial lamb and I was it. That was the understanding. I guess I was butting heads with them a little bit because I was needing more specific information than I was getting and I guess I wasn’t working for them. I think Roland just let the whole thing go and hoped for the best. Him being English and just hands-off and overly respectful. I think a very good producer would have rolled their sleeves up and got in there and [done] whatever had to be done to make it work.

RH: Right.

PL: I remember the editor, Mark Goldblatt. [I was] sitting with him one day after work looking at dailies [and he said] “These guys have all the tricks of the trade. It’s all tricks and no trade.”

RH: (laughs) We’ve talked to him too.

PL: So, what does Mark remember?

RH: Well, he remembers a lot of the problems on the set and particularly the end of the production where he basically had to cobble together the movie because Rocky and Annabel left the project. Dean Semler, Chris Woods and David Snyder all had to start units to finish the film. They had to fill in the pieces for Mark to finish the film at that point.

PL: Yeah. I remember Mark having big lists of shots he needed to make things work.

RH: Right. I think he said that they just didn’t have coverage of things, like the footage they had was just the same thing over and over. He wouldn’t have a lot to cut to or away from.

PL: That’s right. You can’t cut from a wide-shot to wide-shot. No matter how good it might be and how beautiful you made it, you can’t cut a scene with just wide shots. It was stuff like that, all the time. And if I tried to point it out to them on set, they would get quite irate “…what’s going to happen? Are the ‘movie police’ going to come for us..?”

“What's going to happen? Are the 'movie police' going to come for us?”

RH: I think one good thing he said is that there was a lot of ADR done and that any time there was a big establishing or something where they could squeeze some information in they would have a big wide shot that they would record dialogue over just to kind of make sense of the story because it just wasn’t in other places where it could have been.

We have a lot of the scripts, but one thing that everybody kind of doesn’t like about the film is that the very first thing you see: the animated intro. That wasn’t in the script or initially planned. We found out that that was added because the producers felt that the concept of a parallel world just wasn’t tracking with the audience, so the animated intro is what they came up with at the last minute to basically just spell it out.

PL: Yeah, it came across like that, right.

RH: We’ve also talked to David Snyder and he had a lot of good things to say about you and the professional way in which you handled your departure and Semler coming onto the project. He said that you stayed on a couple weeks or so after Semler came on just to make sure everything was a smooth transition.

PL: Yeah. Like I said, we had this damn cement factory and were trying to turn it into a studio and futuristic set. So there’s a lot of prep-work in that. They brought Dean in to replace me and I used to assist Dean on documentaries in the ‘70s, so he and I go way back. I just stayed on to overlap with Dean for about three or four days, I think, to give him the benefit of the pre-production and to give him all my notes and to bring him up to speed on what I prepared and got ready. I do remember him calling me at home about a week later and saying “Pete, what do you have to do to get sacked off this thing?”

RH: (laughs) So how does your style of shooting differ from someone like Dean’s? Are you trying your best to cater to what the director wants or do you get to bring your own kind of shooting style to each project, or is it different for each project?

PL: It’s obviously different for each one. I seek out projects where I get to strongly influence visual interpretation and style of the project. That’s the work I seek out. Some directors just want to work with the actors and they want the DP to take care of the rest. The other end of the spectrum is probably someone like Jim Cameron, who knows every shot and every angle of every lens. That’s not for me.

Dean’s work and my work are different. I think I like to use light more dramatically and impressionistically than Dean. I would describe his lighting style as more naturalistic. With cinematographers, as a rule, some are good with the light, some are good with the lens,” and Dean is very good with the lens.

RH: Yeah.

PL: He’s also very good with first-time and inexperienced directors.

RH: Oh really.

PL: Yeah. Look at Dean’s work and [you’ll see] lots of first-time directors. I think a lot of producers are happy to team him up with first-time directors and actors directing. He’s a very charming man and a very skillful cinematographer.

RH: That’s interesting. And that’s also interesting that you mentioned the lighting issue. Is it also that much more different when you’re shooting in something like the cement factory? Had you ever worked on any other film like that? I guess it’s kind of a studio, but it’s this huge indoor location that’s kind of been converted into a studio.

PL: Strangely enough it was not uncommon in Australia to incorporate elements of the location into the script – in some cases, I’m sure people had the location first and then wrote the script around it. So, I was quite on-board with the idea of integrating elements of the cement factory into the story. But, a studio it wasn’t – those concrete walls and floors were very unforgiving and not what you would call adaptable.

RH: The lighting is interesting because you mentioned the way you use it compared to Dean. When you saw the finished film was there anything you saw that made you think, “I would have done this differently,” or “I would have done that differently.”

PL: Yeah. I can see the difference between my work and Dean’s.

RH: Right. Was there anything that you prepped that you were looking forward to doing that was done differently by Dean or just not filmed?

PL: Yeah. I do remember some stuff, but I can’t remember the particular scenes. When you prep a movie you’re photographing in your head, so when you go into production you have visualized how you want to shoot every scene, so when you see what someone else has done with the same material that you were going to shoot, it’s bound to be a let-down.

RH: (laughs) That’s okay.

PL: I probably haven’t seen the film since ’95. When did it come out? ’94?

RH: It came out in May ’93.

PL: That means I likely shot it in May ’92.

RH: I think it says that it was shot in summer ’92.

PL: It came out ’93. I think you’re right.

RH: I’m not sure if you can answer this or not, but a lot of the early promotional materials stated that they planned to release the film during the holiday season, but it ended up not being released until summer of the next year. I wonder if that was just an early estimation or if there was just something else going on in post-production.

PL: I don’t know. My suspicion was that it hadn’t cut well and they needed more time with it.

RH: I also think that the fact that Jurassic Park came out so soon after hurt it because both films were about dinosaurs and featured animatronics and digital effects, yet Jurassic Park was helmed by Spielberg.

PL: That can happen. It happens a lot. I remember I did a picture called Blown Away. It came out two weeks after Speed and suffered at the box-office as a result.

RH: Oh wow.

PL: And no one had heard of Speed beforehand. It was just this little movie that came out of nowhere and it just clicked. Everybody loved it. And then we came out two weeks later with another movie about bomb. The audiences just didn’t want anymore of what they perceived to be more of the same.

"[Speed] was just this little movie that came out of nowhere and it just clicked."

RH: They seem similar on the surface. I see what you’re saying. It’s been really great talking to you. Do you have any final comments or anything else to say before we go?

PL: Not that I can think of. If I can muster up the energy I could look at the film again and see if it doesn’t jog my memory.

RH: That’d be great. Especially that early part.

PL: Okay. If you have any other questions feel free to follow up.

RH: Yeah. No problem. Thanks a lot for the interview!

PL: My pleasure. Good to talk to you.

RH: See you later.