Interview--David L. Snyder (Production Designer) -- Part I of II

Conducted by: Ryan Hoss

Updated: March 25, 2015

Posted: September 23, 2012

David L. Snyder

One of the reasons why I think the Super Mario Bros. film stands the test of time is the fact that the filmmakers tried to create an entire world from the ground up to tell their story. And while the video games may have influenced parts of the world of Dinohattan, I think an incredible amount of credit should go to production designer David L. Snyder. He was able to take bits and pieces from the games and seamlessly make them a part of the cinematic Super Mario Bros. experience.

You can imagine our excitement when we got the chance to interview David. While the bulk of this interview was conducted in September of 2010, much of it has been updated and refined, because David continues to be so gracious with his time and enthusiasm towards our project. We got to meet him in person when he came out to our screening of the film in Los Angeles, and he was as nice in person as he was over the phone.

This interview has been in the making for some time. As it is quite long, we are splitting it into two parts. So, enjoy this first installment and come back soon for the rest!

Ryan Hoss: So, you were telling me that you just watched the film for the first time in quite a while?

David L. Snyder: Yes, from the beginning to the end at your NuArt Theater screening in Los Angeles. I’ve seen clips here and there, but I’ve just viewed the entire film and it certainly brought back lot of things that I had forgotten, for better or for worse. (laughs)

RH: How do you think the film holds up 19-odd years later?

DS: You know, I actually liked it better than when it came out and I suppose that has to do with the passage of time – it was very difficult making the film and so – I enjoyed it a lot more. I had forgotten most of the negative aspects. Every film is tough. I don’t care if it’s a $75 million movie or if it’s a $1 million movie. They’re all difficult.

I now have a 14-year-old son and he is a Super Mario Bros. video game fan. And, as you know and everyone knows, it’s the 25th anniversary of the game, so there’s a lot of curiosity surrounding the film. I could sense at your screening that a lot of fans consider the film a ‘goof.' (laughs)

I attended Comic-Con this year for ‘Blade Runner @ 30’ and Nintendo had a substantial Super Mario Bros. presence there. It was amazing to see how many people like the film because of the vague reference to the game. It was not the film we all signed on for, and I’m sure you’re aware of that. Bob Hoskins, Dennis Hopper and I were under the impression that we were going to shoot the Dick and Ian script when we all came on board.

At some point in pre-production a page-one re-write by Parker Bennett & Terry Runté was published and distributed to the cast and principal crew. Parker & Terry were great guys to work with, however it was unsettling to have to start over again after months of planning one movie, and scrapping it to do a completely different one.

RH: I would assume that this was after Ed Solomon came in to revise Dick and Ian's script rework of Parker and Terry's original.

DS: Yes. Ed Solomon was brought in after the Disney pick-up. I had worked with him on Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey before that. So I had known and liked working with Ed. Once Disney came into the picture the tone of the story went from dark to light, like day & night. It was clear that a decision had been made to turn Super Mario Bros. into a family film. I believe Jeffrey Katzenberg wanted the picture to enable Disney to integrate the Nintendo characters into the Disneyland and Walt Disney World theme parks. I’m pretty certain that it was the stellar cast, the costume and set designs that motivated him to ‘buy’ the picture. When he arrived on the set we staged a ‘parade' of the cars, costumes and sets for him and he appeared to be impressed.

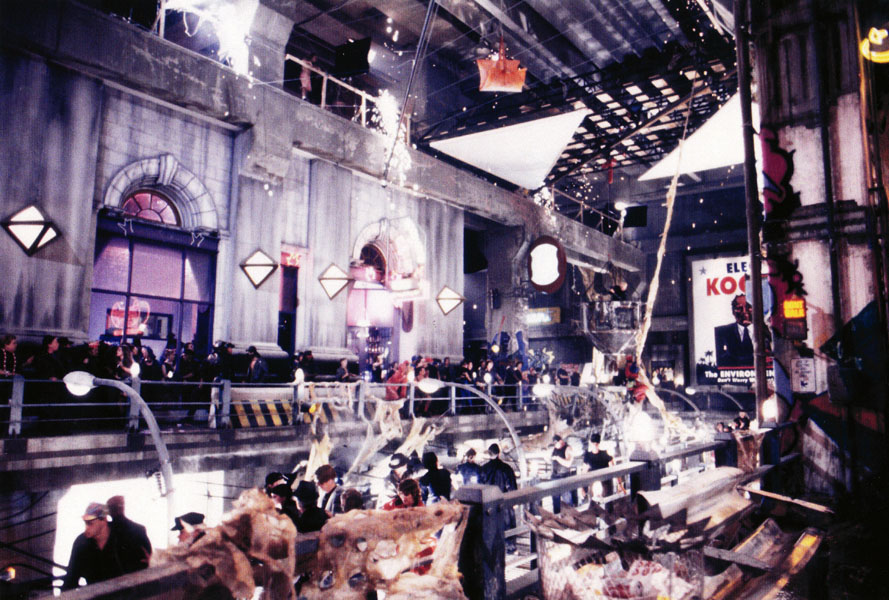

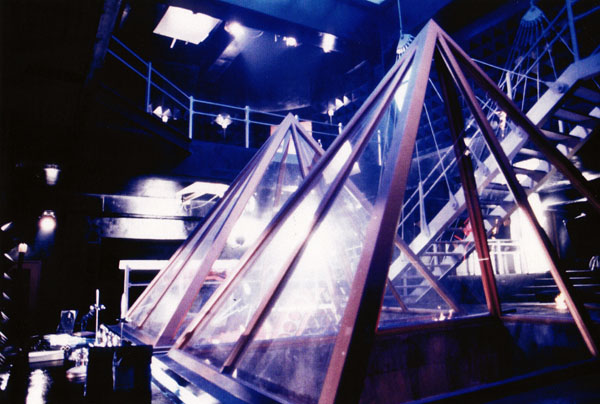

The space they gave me to work in was enormous and made of reinforced concrete so, generally speaking, when you construct a set a lot of the money goes into just building the structure to hold the sets up, whether it’s steel scaffolding or whether it’s wood framed. So what I was able to do was go into the existing architecture and hang the sets from it, filling in the spaces between. It was a great location to work in for me; I don’t know about the shooting company crew and the actors because, you know, it was kind of ‘grody’ in The (less than) Ideal Cement Company plant.

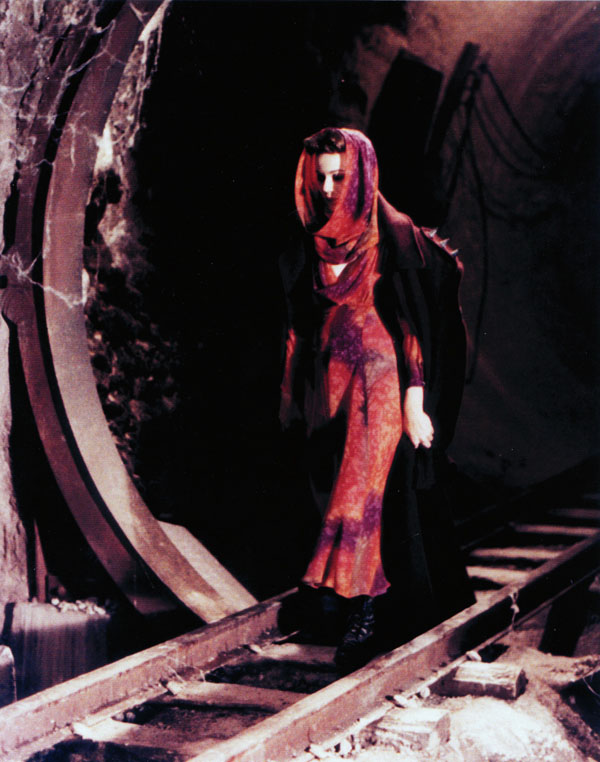

This was the structure for the meteorite chamber

RH: (laughs)

DS: As everyone knows, there were issues about safety and health concerns, but I just got into doing my thing and didn’t think too much about it. SMB had a great art department. Patrick Tatapoulos, who is now a director, was a conceptual artist and he ran the creature shop and went on to do films like Godzilla. Simon Murton, Beth Rubino, Tom Valentine, Sarah Knowles, Melanie Baker, Tim Galvin, Claudette Didul, Robbie Consing – the whole art department was amazing. It was very difficult because it was like 100+ degrees and 100+ humidity. It was miserable to work there but looking back on the experience it was a lot of fun.

When the Disney Company decided that they would distribute the film, the tone of it changed in the sense that they wanted to make a family film, which is the Disney trademark. It didn’t change everything that I was doing, but the story was sort of a compromise between the different scripts and I think it goes off the rails now and again. As I watch it today, there’s a lot of clever dialogue and sight gags. And of course the cast. The inimitable Bob Hoskins, the incredibly talented John Leguizamo--everyone. Fiona Shaw, Samantha Mathis, Fisher Stevens, who I’ve known since he was 19-years-old when we did My Science Project together with Dennis Hopper at Disney. I recommended Fish to [directors] Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, they met with him and hired him. I think the Spike and Iggy stuff is some of the best bits in the film. Especially when they’re evolved.

RH: Definitely!

DS: So as I was saying, it was a great Art Department. Fred Caruso, who literally ran the show for Roland [Joffé] and Jake [Eberts] had a lot of experience (i.e. The Godfather) and everything that followed it. Fred is a uniquely talented producer. When it came to the art department budget--and we would have to discuss it--he was always fair. I recall one such occasion when I was obliged to ‘beg’ for more time and money, and Fred made a sad face and said “David, you know no one loves this movie more than me, but ‘no,’ you cannot have any more money." (laughs)

He had a great skill about making you feel OK about no more time and money.

"I think the Spike and Iggy stuff is some of the best bits in the film"

RH: Speaking of shifting schedules, what had been shot before Dean Semler replace Peter Levy as the director of photography?

DS: We started out in some smaller sets. The first thing that we shot was Mario and Luigi heading on their way to a plumbing emergency call to repair a leaking dishwashing machine at a restaurant. They just pull up in the plumbing truck, get out, and they see Scapelli’s truck, and they ‘cut.'

RH: That’s it?

DS: Yes. We spent the day inside a restaurant kitchen location as Mario and Luigi attempt to fix the broken machine, shooting beauty shots of soap bubbles and inserts--things you would do in a commercial. To my recollection, it never ended up in the final film.

RH: No, it’s not.

DS: While we were building sets we shot some local locations in Wilmington ‘as’ Brooklyn, New York. When were shooting those scenes you could hear – (laughs) – Bob Hoskins over the radio mic as they were driving through the streets of Wilmington: “Is this supposed to be Brooklyn?” You know—disappointed. (laughs)

It was actually embarrassing for me, you know, because I’m the production designer of the picture.

Notice how much personality is present even in the 70s Brooklyn setting

RH: I'm sure it was!

DS: He and John Leguizamo were joking about that during the recording of the scene before the slates (scene markers). Like, “What the hell is this? This isn’t Brooklyn, is it?” This subsequently led to me being sent to Brooklyn to direct a second unit of all the Brooklyn stuff, which I shot following the completion of principal photography.

RH: Not a bad outcome...

DS: So I went to Brooklyn, Chris Woods shot second-unit visual effects, Dean Semler shot a main second-unit and Jimmy Devis shot an ‘action’ unit. At the end of so many days, Roland & Jake said “Thank you, goodbye” to R&A and so we had to go out and shoot the missing pieces as best as we could. In all fairness to R&A, I believe that Disney coming into the picture is probably what changed the direction of the film, causing it to go slightly off-course in more than one direction.

RH: I agree completely.

DS: I read Jeff Goodwin’s interview and I was really happy to see it because I hadn’t seen him since. It was really great to revisit him.

RH: Yeah! No problem. His interview was really cool. He had all these great pictures and information.

DS: Yes, he and Fred Caruso hired my daughter Amy to be his assistant, which was a great job for her being so young at the time.

RH: Wasn’t she in the makeup or hair department?

DS: Yes, she was a makeup artist. She had worked before and had been trained, but she was in her early 20’s at the time. It was a great job for her and Jeff was really good to her and I appreciated the fact that he was. Right now she’s working on Private Practice. She works all the time. She’s been very successful and I think a lot of it had to do with Jeff helping her learn. So, I appreciated it.

RH: That’s great to hear. He’s been great answering all my follow-up e-mails and things like that. But, I think tomorrow we’re gonna be talking to Richard Edson.

DS: Oh, yeah, sure, Richard. He’s great. He’s a musician, I think, and an actor. I think he plays bass in a band, or he did at the time.

Hair and makeup also had a significant impact on the look and feel of the film

RH: And before I started asking more questions I did want to mention I do have a lot of SMB stuff. There was an auction a couple years ago that had a bunch of storyboards, a prop newspaper, a Goomba patch, [and] the before-and-after shot of the cement factory.

DS: Oh yeah. Profiles in History, maybe. Yeah.

RH: Yeah, exactly. That’s it.

DS: Yeah, I had quite a bit of Blade Runner and Super Mario Bros. material in my archives. As a matter of fact, at this point right now I have so many boxes of memorabilia, that I’ve made arrangements to donate my paperwork to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which I’ve been a member of since 1983. I can’t bear to throw it in the dumpster, but I can’t keep it forever. A lot of paperwork , sketches and photos.

Editor's note: David's archive was delivered to the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences on August 21st and when organized can be viewed at the library as the David L. Snyder collection.

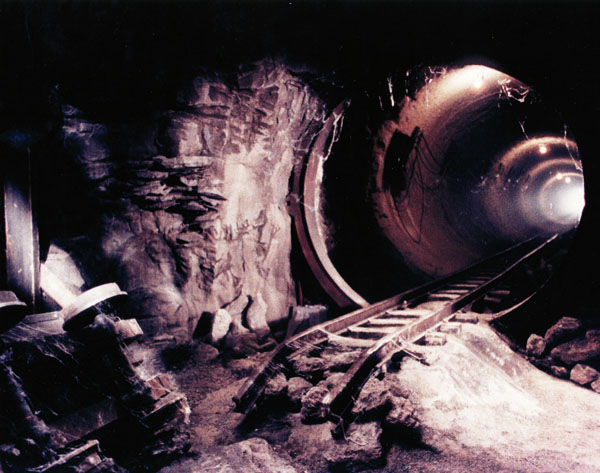

RH: Yeah. I mean, I really like this stuff that I got because it’s really great, especially the before-and-after picture. It's incredible to see how much effort went into transforming that cement factory into the final set. It was just really great to look at.

DS: Yes, thanks. Unfortunately, the story just wasn’t there. But it’s a cool movie to look at. I think the 'Cadillac Ranch’ inspired set [hanging by fungus] for the Parking Violation Sector at the Koopa Square Subway Stop is one of my favorite sets in the film. That was pretty sick in concept and in the realization of the design.

This area is one of David's favorite sets in the film

RH: It’s kinda like Blade Runner, in some ways. There’s just so much going on that’s it’s so fun to go back into the film and pick out all those little pieces, all the video game references and things like that. Those little details is really what makes it full of life and energy. Unfortunately, for us fans there’s not a high-definition version of the movie out. All we have is a lackluster DVD transfer. We wish we had a better version of the film so we could see all this stuff in even more detail.

DS: I don’t know if they have any plans on doing anything with it, but I just looked at it [the DVD] and I noticed it was kind of weak in its resolution. It’s not great. It’s not great at all. The difference between Blade Runner and Super Mario Bros. is that Blade Runner [was] inspired by what we thought the future would be--which had a lot to do with Syd Mead’s industrial-designs because he’s a "real world" person.

In Super Mario Bros. it’s strictly fantasy, you know, like Bill and Ted Go to Hell (aka Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey). It’s fantasy and Blade Runner is industrial-design/futuristic (or at least what we thought it would be). So they’re both interesting to look at, but in a way Super Mario Bros. was a lot more fun because there weren’t any rules about what the future would be. It’s just a parallel universe that sprang from our imaginations.

RH: I think one of the really interesting things about the film is how you and the production team took the existing structure of the cement factory and made the sets around it. Was that a creative hindrance or did it end up helping in some ways?

DS: Well, first of all, the cement plant was closed and it was never going be a cement plant again so there wasn’t anything much in the way of restrictions. You go to Warner Bros. Stage 16 and you’re not going be cutting a hole in the stage wall or the floor. Basically, the whole realm of our universe--Dinohattan aka Dino Yawk--is in a state of decrepitude and destruction. We had the freedom to drag tools, equipment and material into the plant and we could do just about anything we wanted to do: acetylene torches, minor combustion effects, explosives. A lot of those things you can’t do on a sound-stage without approvals, time and money.

The unrestricted nature of designing sets in the cement plant freed up resources for extra effects

RH: Well, from all the research we’ve done it seems like the producers started out on Super Mario Bros. with a completely different vision. They had a different screenplay [that] was much, much more fantasy-based like the games. That was quite a bit before Rocky and Annabel came on board. Do you know anything about when that changed or what it was like when you first came onto the project?

DS: Well, Fred Caruso and Chris Woods were there with the guy who directed Mom and Dad Save the World. Greg Beeman. As a matter of fact, I met him and Michael Phillips, the producer on that film too. So, in any case, I came in and I met with Rocky and Annabel. They had just taken over the film and they told my agent, Debbie Haeusler, that they took a ‘pass’ on me because they were afraid that the film would look too much like Blade Runner or Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.

So, they hired a very talented and renowned production designer who worked out of Montreal and Paris. His name is Wolf Kroeger. Wolf started the show and Patrick Tatopoulos was there, Simon Murton was there and the storyboard guys were there. There were a few Art people on the show and the next thing [I heard] was that Wolf had a dispute with the directors. They had come into his office and started to sketch on a drawing that he was working on. I was not present, but Patrick and Simon Murton were and it went something like, Wolf said “I don’t write in your script and you don’t sketch on my drawing,” and I was informed he resigned.

And then I had a call from Fred Caruso – and this was just like within weeks after the first interview – and I met them again. Roland Joffé had already fired one director and now he was going to have to fire a production designer. I had to meet with him because he wanted to make sure that I was “okay,” as the picture was getting off on a bad start. Needless to say, as Roland and Jake were sort of financing the film, guaranteeing its completion, meaning they were responsible for the money, as well as its success.

So, I met with Roland and he approved me and Fred said “great” and I was told by Rocky and Annabel that they were hiring me because they “loved the look of Blade Runner and Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.”

Koopa's apartment before...

RH: (laughs)

DS: I thought to myself “Okay. Well, they’re going to pay me a fair amount of money and it’s going to be a long run.” I had no personal engagement in the game itself, but I liked the idea that it made children happy. Kids loved the game. I thought “Well, I like kids. I’ve had a few kids. [Note: 4] I’ll work on a picture that my kids can go see as opposed to the murder and mayhem seen in some of my other films. So I took the job and when I started and I kept everyone who preceded me in the art department. I didn’t replace anyone, but we started all over again. Wolf's designs were all put aside and I did what I felt was aesthetically appropriate.

Basically, the original design of the film was loosely based on the game's characters and environments. Inasmuch as we did not know if we were going to construct these sets or where we would construct them, we were going to have to find a location or a stage large enough to accommodate us. The cement plant wasn’t even in anyone’s imagination at the time because we hadn’t scouted it or hadn’t even seen photographs of it.

So, I got on a 737 with Fred & Rocky and headed to Houston, Atlanta, and finally Wilmington, NC. I have a memory that Annabel was finishing a commercial for their company, Morton/Jankel/Zander aka MJZ.

I was very concerned about the construction & paint department when I first arrived in Wilmington. I had worked with the guys who built Heaven’s Gate prior to building Blade Runner--Jim Orendorf and Jimmy Woods. I was accustomed to having the best people. I didn’t know what to expect, going to North Carolina. There I met Jeff Schlatter, who was hired as the construction coordinator and he was great. We had so many talented people on his crew. Production designers only have ideas and schemes but at the end of the day someone has to get the tools and equipment, buy the material, load it in trucks and realize these ideas. Well, to my delight and my surprise, everyone there was great. These guys were out to prove that they were as good as anybody else and their work was superb for that reason.

...and after

RH: In my opinion, you can really tell that, looking at the film.

DS: Listen, a lot of people who worked on that show in the art department have gone on to be successful production designers and set decorators. Talented people who were recruited from the entry ranks of the art department have gone on to do great things on their own, beyond me. So, that’s how it started on SMB. Wolf Kroeger was happy to leave and they were happy to get me...I think.

RH: (laughs)

DS: We did the apartment sets first. See, you always start out with the sets you can stand up quickly. We built the Mario & Luigi apartment on-stage to match the Wilmington location which was standing in for Brooklyn. We also rented their flower shop sign and removed it from the building and installed it on the stage exterior window to match. As I look at it today it’s a fairly good-looking movie with much of the credit going to Beth Rubino, who was a first-time big-budget decorator. We had met on a set in Atlanta, Georgia by chance. We were in town on a location scout where she was decorating Trespass, a Walter Hill film. I liked what I saw.

So, I decided to hire Beth on the spot and Fred Caruso said “Okay”. She’s gone on to win two Academy award nominations and an EMMY nomination. She’s delightful. She’s a great decorator and friend. I was lucky to have her, [as well as] Sarah Knowles, who started out with me as an art department production assistant. Sarah went on to win an Emmy Award for the F.D.R. biography Warm Springs with Kenneth Branagh, for Best Art Direction. I’m fairly good at finding talented people. That’s one thing I can do.

And, of course, they weren’t paying a lot of money, so when you don't have a generous budget for Art Dept. personnel, it’s hard to get experienced people. You get people that you believe in and you teach them and train them. I really enjoy being a mentor because I was mentored by Lawrence G. ‘Larry’ Paull, who production designed Blade Runner, Back to the Future, Romancing the Stone and 1941. So I believe in that system. Promoting from within.

RH: I think that’s totally accurate. In my opinion the film succeeds from a visual standpoint. The production design was wonderful, the effects for the time were really good, and all the practical stuff--like the animatronics--those are great.

DS: Oh yeah. Are you kidding me? Man, you should have been there to see it all go down...

RH: I wish I was. (laughs)

DS: Regarding the animatronics, I had my own thing to do and I had little to do with the success of Patrick Tatopoulos’ unit. I was amazed at everything they did and I would stop in once in a while when I had a minute, which wasn’t often, just to see what they were doing because I was interested as a fan, not as the production designer.

I think Patrick is one of the great creature-designing talents in the industry and when he decided to become a production designer, I introduced him to my former agent Paul Hook at ICM. Patrick had called me on the phone and he said “David! David! I’m going to design a film (Independence Day)! I have to meet with you! I don’t know what to do!” So we met, and unfortunately for me, it meant the end of our days working together. He had, as they say, left the nest.

RH: (laughs) I mean, we’d love to get into contact with him, somehow, because it seems like he was also on the earlier fantasy-based production before Rocky and Annabel came along, so it would be interesting to see what he planned on designing for that part, too.

DS: Yeah, I think his biggest deal on that was Yoshi. And he also did a lot of graphics for me, too. He would paint posters that we would use as set décor: advertising art [depicting] half-human half-dinosaur women, Dino-babe pin-ups. Really cool illustrations. He was great at that.

RH: So when you were signed on and all set, what kind of direction did you initially receive from Rocky and Annabel in regards to what they wanted the film to look like? Did you get along in that regard?

DS: They were an intelligent, talented couple. I liked them very much and I was just happy that they chose me because [if] it was good for me [and] it was good for them [then] it’s going be good for the movie. The beginning was no more than a lot of storyboarding based on the way the script was written and re-written, but mostly location-scouting. We’d fly here and we’d go there, and we really couldn’t go much further because I was given the task of creating an entire city--an entire universe, really. And until I had the space to do it in – I mean, we had ideas, and, as I said in the New York Times, I pointed out that everything that we did in the other universe had to do with the fact that there was just a different twist on it because it’s a parallel universe. We tried not to be too mean-spirited about it so that it would be a fun ride popcorn movie based on the fabulously popular video game. R&A created helpful glossaries and and lists of how the video game elements would be woven into the film.

Goombas? Thwomp? Sounds good to me

RH: Oh really?

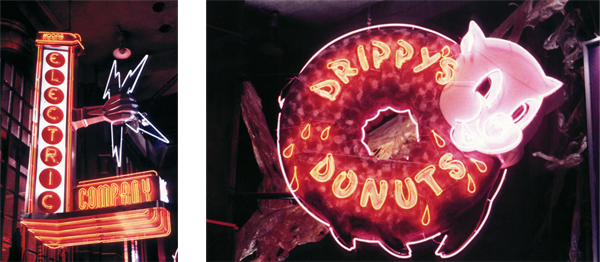

DS: Yeah. R&A provided a vast amount of helpful information that was published and distributed about what they wanted us to do. They composed many lists. There was an ample amount of time spent on signage and graphics, like “Drippy’s Donuts” and “Koopa Electric Company” evolved out of the idea that he ran the grid. Koopa was in charge of everything. Dinohattan had little water and the city was out of control, kind of like it is now. There’s one thing it has in common with Blade Runner; basically there is no apparent authority in charge of the general population. Koopa is essentially a dictator with an armed police force, the Goombas.

We began design and set construction. Numerous sets and neon signs were all drawn up. We had hundreds of drawings that were produced manually; pencil and marker on vellum, as opposed to Photoshop™, CAD and Illustrator™ etc. We didn’t have access to any of those tools on this picture, so it was very time-consuming.

So, the drawings were completed and I signed off on the drawings with R or A’a approval. Then one of the directors would go out of town to do a commercial and then come back to town. The sets would be under construction and one or the other would say “Well I didn’t approve that”. Then one or the other would say “Stop doing whatever you’re doing. We’re going do it over again.” It was costly and fairly exhausting.

At this point Fred Caruso, being the show-runner, had to step in and sort of take total control of the picture.

RH: Oh wow.

DS: R&A appeared to be at crossed purposes at times. And, you know, they were lovely people to go to their home and have a meal with them and their two children, toddlers. Yet, somehow, they just couldn’t come to terms with each other about what to do next.

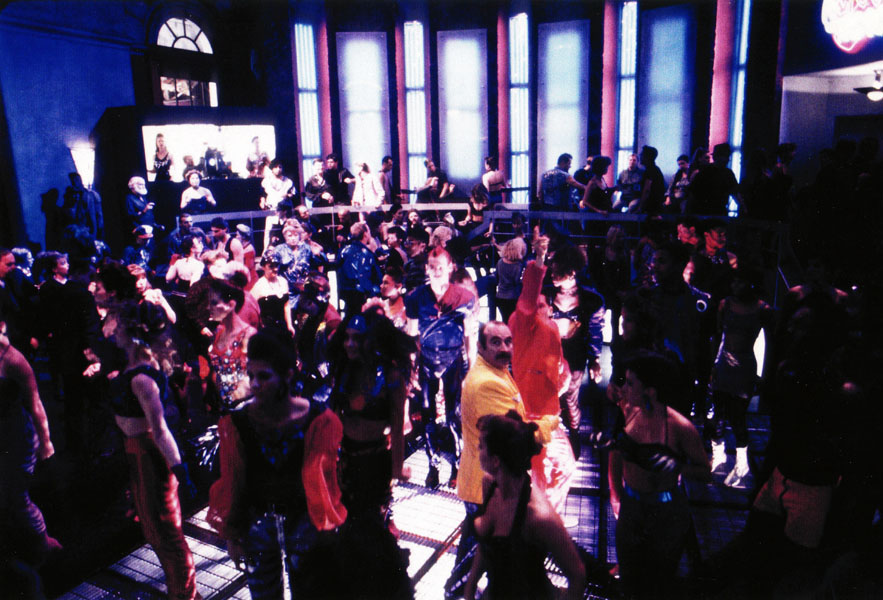

I remember days sitting in dailies where you’d see Bob Hoskins and Johnny Legz on-screen standing in the Boom Boom Bar set before the 2nd A.C. (assistant camera) ‘clapped’ the slate. Over the radio-mic you’d hear Bob say to Johnny “Do you know what we’re doing?” and John [would] say “No. Do you know what we’re supposed to do?” and [Bob would say] “No. I don’t know.”

So, as they were standing there ready for direction, R&A would be weaving around the crowd of extras fixing their hair and adjusting their costumes and doing all the things that the set decorator, the prop-person or the costumer might do.

So, they spent a lot of time on the visuals, which were dazzling and they always enhanced the ‘frame’. They were extremely talented and creative with the film’s visual details. Brilliant.

"Drippy’s Donuts” and “Koopa Electric Company” evolved out of the idea that [Koopa] ran the grid."

RH: (laughs) Yeah, I’ve heard about that.

DS: My wife Terry is an actress (she appears in the film as the Hatcheck Girl) and she and Bob, Fish, Johnny Legz, Samantha Mathis, Fiona Shaw and, well, the entire cast would go to Wrightsville Beach in Wilmington and perform Shakespearian works. They created Shakespeare Sundays because they were unhappy with the way the movie was going. This was no secret.

They said “Let’s just get through this.” Dennis Hopper was angry. He called R&A “rebels without a clue.” You know, it was mean, but the actors were frustrated because they had come onboard expecting the film to be directed by methods they were accustomed to.

So, in the long-run--in the big picture--it was great. Now many fans seem to have embraced the film. I’ve designed films like, Strange Brew and Bill & Ted that were not well-received, yet are considered cult films.

RH: That’s something that’s really happened over the past couple years. A lot of people are either revisiting the film or are experiencing it for the first time and only now people are starting to appreciate the movie. I’m sure that back then one of the reasons it wasn’t well-received was because people just couldn’t see the relation to the game. I don’t know if it wasn’t marketed that well or anything. It’s definitely risen in popularity over the past couple years especially.

DS: When we had the World Premiere at the Disney studios in Orlando, Florida, there were no executives of note from the studio in attendance. That was a bad sign. The next time I saw the movie was in Michael Eisner’s screening room. Michael was there, Jeffrey, Fred Caruso, Maurice 'Mo' Lospinoso, Louis D’Esposito, the first AD (who is now the co-president of production at Marvel Studios) and of course R&A, the directors.

I think that Disney did whatever they could to try to save the movie. One thing the studio did that seemed a positive start was they opened the picture at their flagship theater, the El Capitan, in Hollywood. The only pictures that play there are their tentpole movies such as the Toy Story franchise, but that was it. The End.

[Dennis Hopper] called R&A “rebels without a clue.”

RH: Yeah. Well, I guess with Blade Runner – and Super Mario Bros. to an extent – it was almost ahead of its time in what it tried to do. It’s one of those movies that comes out that’s not really understood by the average filmgoer until quite a bit later.

DS: You mean like The Wizard of Oz, which initially was a flop? By the way, as tough as it was on Blade Runner, I was very confident that it would turn out the way I had imagined. I’m very proud of the film. I think it looks great. I think it’s a beautifully-constructed film. Aside from my work under Larry Paull's direction, I think that the craftsmanship that went into it and the way that it was lit and photographed is amazing.

In regards to Super Mario Bros., I’ve always said that the thing that astounds me is that whoever wants to take the responsibility, actually took the most successful video game in the history of video games and not only destroyed a movie about it but in turn destroyed the franchise to make more.

Because at the end of the movie it’s obviously set up for the sequel. Daisy comes running in the door and they’re off again on another adventure. They made like, how many Batmans, how many Supermans, how many this, how many that sequels? Even Keanu and Alex are talking about making a third in their franchise, “Bill and Ted 3D”.

RH: Yeah. And it would be fun. People would love to see that again.

DS: Oh yeah. Bill and Ted in 3D is a great idea.

RH: So, like you said, they did open it for a sequel. Do you know if Rocky and Annabel had any ideas for a sequel or if anybody discussed any sequel options before the movie was released? Were there any ideas around for it?

DS: Rocky and Annabel just wanted to be finished with the movie. Now, I’m sure that the Disney Company and Nintendo had a notion about SMB being franchise. I’m sure that’s why Jeffrey got into it.

I mean, look at Dreamworks Animation: everything has a sequel. At least one. And if not in theaters, then a DVD for the third one. They keep making them. And Super Mario Bros.; how could it miss? How could they have not considered having Bob, Johnny Legz, Dennis and everybody else who was in it? It was a sure thing.

RH: You know, that’s pretty disappointing considering they were the ones that had that concept. It’s a shame they weren’t able to carry it out to the fullest without the problems that there were. After they left the project – you said you and Chris were on second unit – but didn’t Dean end up finishing the bulk of the rest of the movie after they left?

DS: Dean shot everything at the studio with the Goombas, Jimmy Devis had an action unit in Wilmington and Chris Woods had the visual effects-unit with Bob Hoskins. The reason I was sent to New York wasn’t driven by a story point; it was just “Let’s send David to New York to get Brooklyn in the movie”.

So, I had one day, from sunrise to sunset, one camera and ten people and that was it. No lights, no sound, just one 35mm Panavision camera. I got out on the streets, got the camera department together and went to Brooklyn and all those shots in Brooklyn really make a big difference. Especially when they drive by in the SMB Plumbing Truck as the camera pans along Fulton Street. The shot ends on the Brooklyn Bridge looking across the water at Manhattan. These shots added some essential Brooklyn atmosphere to the film.

"And Super Mario Bros.; how could it miss?...It was a sure thing."

RH: Well that’s the thing: You were saying how heartbreaking it is to realize these things, but what we’ve been doing with the website is really digging into the film and finding all this stuff that was planned but cut. It’s so upsetting because it seems like there’s a lot of really great stuff that just didn’t make it. Could you elaborate on any of the deleted scenes or things that were cut or maybe even sets that you had to build that aren’t in the movie or anything like that that you think would have made the movie better?

DS: For the most part, I must say that all the things that Dean and Peter shot were great. I was never unhappy with the angles or the sizes of the shots... Except at the very end of the shoot, the very end days.

We shot in order where they’re on the bridge and they see the Bob-Omb and Koopa is in the cement bucket: none of that was ever planned to be that way. It was much more elaborate than what you see [on film], but by that point not only were they unhappy with the film but we were running out of time and money. They’d say they can’t even remember what that bucket was supposed to be before it became ‘the bucket’.

The joke was, like New York City, there’s always something under construction, except it’s apparent that there’s no workmen doing ‘business’ there and it’s just this ridiculous hunk of iron hanging in the middle of the set. It’s terrible.

RH: Yeah, and you never see it beforehand.

DS: Yeah. It’s just senseless. The biggest disappointment to me was at the very end. The end of the movie was just glued together in my opinion--the entire sequence of the confrontation between Mario and Koopa.

The only good thing about it was Chris Woods’ work on the particle effects, you know, the disintegration / teleportation sequence where Koopa morphs from Dinohattan to Brooklyn and back.

The climax battle is so cheap that I can barely stand to watch it. I mean, I like the end-end when Mario and Luigi are reunited with Daisy and they’re all cheering victoriously. I also admit I liked the cliffhanger epilogue.

RH: That totally jives with what we’ve heard about the end of the film being shot at the tail end of the shoot.

DS: I think somebody should attempt to re-cut the film. Just lift out or trim the scenes that are ponderous. As far as I’m concerned, I wouldn’t cut anything with Spike and Iggy. It’s all great including when we first see them on the streets of Wilmington ‘as’ Brooklyn as they’re futilely attempting to kidnap Daisy.

A light at the end of the tunnel

RH: Yeah, they’re great characters.

DS: It’s hysterical.

RH: Do you remember what was originally planned for the climax? According to Parker and Terry’s first draft and Dick and Ian’s draft, at the end of the movie Koopa turns into a T-Rex lizard-monster and they return to New York to fight on the Brooklyn Bridge, with Koopa walking on the bridge as the lizard-creature. Does that ring any bells?

DS: Yeah, you know, it does ring a bell. I was going build a chunk of the Brooklyn Bridge on-stage. I had forgotten that. We had drawn up the plans, but time and money got the best of us. Too bad. It was a cool idea.

So yeah, that would have been a better ending but I think at some point they just said “You know what? Everybody who ever played Nintendo Super Mario Bros. will go to see the movie.” Well, what they didn’t count on was everybody who had ever played the game that went to see the movie in theaters would hate it because it was nothing like they thought it would be. They were disappointed in it.

But now that generation has grown up and I think they have a fondness for it because it’s nostalgic. [They’ll say] “Oh yeah, Mario Bros. I saw that,” and all of a sudden they’ll take their kids to see it and they’ll rent it on DVD or On-Demand.

Now that a good amount of ground has been covered, check back soon for PART II!