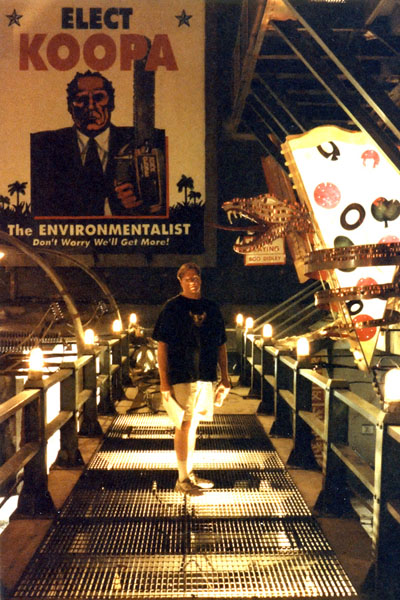

Interview--Parker Bennett (Screenwriter)

Conducted by: Ryan Hoss and Steven Applebaum

September 18, 2010

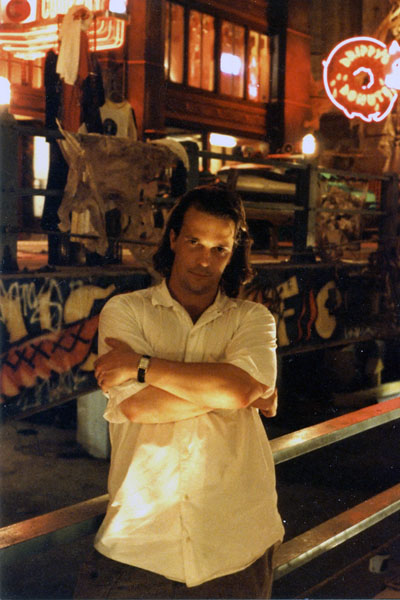

Terry Runté (left) and Parker Bennett (right)

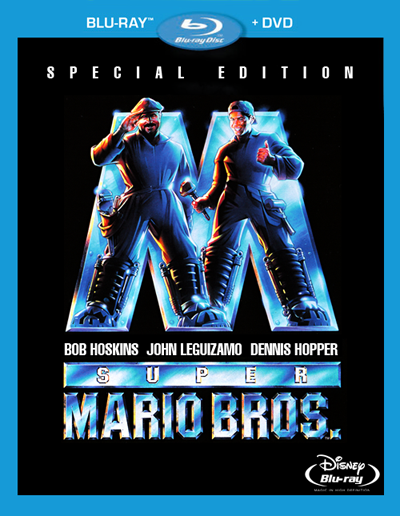

Parker Bennett and Terry Runté were given the daunting task of wrangling Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel's revitalized concept for Super Mario Bros. into a cohesive story. Their creativity and drive to make an intriguing screenplay led to an intense collaborative effort with the directors, resulting in a story that laid the foundation for the rest of the project.

While Terry is unfortunately no longer with us, a piece of him lives on through Parker's detailed look back on the film's creative process. Read on and learn how they helped make the film into what it is; whether an instant failure or an eventual success, they tried. No one can deny that.

Ryan Hoss: Parker, this is great being able to talk to you about your work on the film. We’ve enjoyed all the documentation you’ve sent so far, so hopefully we can find out even more about the whole development process.

Parker Bennett: Well, as I wrote to you guys, it was 20-plus years ago, so it’s a little vague in my mind and I’m not the final source for a lot of this information. But, I’m happy to talk!

Steven Applebaum: Well, since you and Terry were the first to work with Rocky and Annabel on creating the film’s world and backstory you should hopefully have some final say on our questions.

PB: Well, I have to give credit where credit is due. The whole idea of the parallel world and the dinosaurs evolving into people: that’s all Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel. They had this great take on the underlying concept of the movie. It was totally from them. We met with them and we knew their work from before because we were both from advertising, Terry and I, and these guys did a lot of commercial shoots. We knew their work from that.

We also had a shared experience in that the first movies we were involved with were both with the same producer, Cathleen Summers. So, when we met we had a chance to chat about that and we just really hit it off. And we kind of bandied around a lot of ideas back and forth when we first met. Then Terry and I went back and we put together this little pitch document, because we didn’t really get far into the specifics of what we would do with the movie. And I think Rocky said later it was the drawing on the front of it that got us the job, not so much the story that we worked out.

So, we got the job and we started just holing up with the directors and batting ideas around and trying to come up with a structure for the story.

RH: Cool. So, Rocky and Annabel basically had the core concepts for what they wanted their film to be, but not so much the story, right? They knew what they wanted the world and characters to be, but they didn’t really know how to take the story and how it related to the games?

PB: Now, all that got worked out over like a six-week period. There was an office on Robertson Blvd. that Lightmotive Entertainment had set up and there was an upstairs office, which was a big space with a lot of bulletin board area. And we just put ideas up on the board day after day and kind of shaped it until we figured out what we wanted to have happen.

And during that time we learned a lot about what had come before: The art department was still working on the last version of the script, the Jennewein/Parker script, so there were storyboards and drawings and clay models of the bricks that would come falling down, they were talking and stuff.

So, it was a weird time, because things were shifting and the producers were very concerned at this point because I think they had spent at least a couple million dollars in developing the previous versions. With Barry Morrow they spent a huge amount of money to get the first draft and they got pretty far into this Jennewein/Parker production before they shut it down, so they were really behind the 8-ball already, budget-wise.

As a result, we got a lot of input from the producers to scale back what we wanted to do and I think Terry and I and the directors were not very cooperative on that.

RH: Oh, okay.

PB: I just took a quick look at our script, and it was like, wow: There’s elevated trains crashing down and huge explosions and there are giant – just huge – set pieces, so we obviously were not paying attention to the producers. As a concession, I think we kept a lot more of our story tied to the “real world,” trying to have a story with Mario and Luigi and the mobster-plumber guy.

RH: Yeah. Scapelli.

PB: Yeah, Scapelli… I think that was more central to our script. I don’t really remember how it all turned out, so, again, you’ll have to forgive me. I will say that Scapelli is named after my old advertising boss, who was Bob Scarpelli.

Interviewer’s note: Scapelli was originally named “Scarpelli” in Parker and Terry’s initial script.

RH: Right. It seems like there was quite a bit more to the story in the first act of the film regarding Scapelli and his rivalry with Mario and Luigi. It seems like most of that was filmed only to be cut to either trim the runtime or just to get Mario and Luigi into the parallel dimension sooner.

PB: Yeah, you know, the editor [and I] became really good friends. Mark Goldblatt [the editor] and Caroline Ross was his assistant. When we got to the set we used to hang out over there a lot.

So, they had a big challenge to make a movie out of what got shot, because, let’s be frank: it wasn’t a coherent script. Ever. (laughs)

RH: (laughs)

PB: It was our draft and then-(stumbles, thinking)

SA: Dick Clement and Ian la Frenais.

PB: Dick, yeah. Clement and la Frenais did a draft. And that’s what got people like Fiona Shaw on board. It was a much more character-oriented draft and they were working on that. (sighs) I don’t know if I ever got to read their draft. I think when we were coming down to the end and we were trying to make the case for getting screen credit-I don’t think I ever read their draft. I think they probably contributed more than I gave them credit for, at least in terms of tightening things up and shifting the basic structure around.

But, it was totally Ed Solomon who did the shooting draft. Most of the dialogue and the final shape of the movie was from Ed, and I think Ryan Rowe worked with him for a while. And I know he had to do it in a ridiculously short amount of time. It was like he pulled a “three-day, stay-up-all-night” kind of thing. And he did it within probably ten days to get the shooting script done.

RH: Wow.

PB: While they were doing all that, the art departments were working on the constants that were basically in our draft and in the subsequent draft from Dick and Ian. Everything was kind of restrained by the art department, which was already moving ahead, so they had to have certain elements that were already there because they were building the sets and they were creating the creatures and all that stuff.

I know that the editors really had their work cut out for them to bring it together. And I’m sure cutting out the first-act stuff that was set in our world made a lot of sense because it’s just too much story. You just lose track of that. You don’t care about that after you get into the dino-world. So, it makes total sense to get rid of that stuff. And we probably would have gotten rid of it too [given another draft]. I think that was from the producers trying to keep the production more grounded.

RH: Yeah.

PB: Am I making any sense? I feel like I’m rambling, sorry. I mean, the directors basically had the final say on everything going up to and through the bulk of the shoot, and then the editors finally had to turn it into a movie, but “what was the story” was really in flux all the way through production and into post-production.

Terry and I wound up going back and we did this incredible amount of looping, because the story wasn’t quite tracking for people – the whole “parallel dimension” thing – the producers were worried that nobody was getting it.

So, we had a situation at the end where any shot that was a long shot or a character turned [their] back, we were putting new dialogue in there to try make the story make sense. The post-production supervisor said that it was the most ADR-looping she’d ever encountered on a film.

So, it was a struggle to make the story come together even as much as it did.

RH: Yeah. There’s one thing that really needed to get across at the start of the film, which was that everything in our world needed to focus on the characters. Once you’re in the other dimension there’s not enough time to really explore them anymore as the film now has to focus more on explaining the parallel world, its society and culture and why the dimensions are split. The story had to focus on that once you’re in the second and third parts of the film. Because most of the opening was cut down the characters are kind of lacking, which makes it difficult to really care about the story once it picks up.

PB: Yeah, I don’t claim that we made the best choices-(starts laughing)-in cobbling together the movie. It’s just that, that’s what happened. And the other thing that happened was, during production, they were so far over-budget that they just needed to make cuts.

You know, we showed up on the set to just say “Hi” and see what was going on and they immediately drafted us. “It’s a good thing you’re here,” Roland Joffe [said as he] came up to us. “We just happened to need a bunch of writers!” I remember Rocky called us their “pencils.”

And so we were drafted in to just look through the script at everything that hadn’t been shot and see if we could make any cuts, anything we could trim or shorten or do less of, because they were so far over-budget.

So, we did that and we did it to the point where Dennis Hopper was hollering at me because I cut some lines of his. Like for half-an-hour he was hollering at me and made Terry and me look up the word “act” in the dictionary.

RH: (laughs) That's hilarious. Do you remember which scene that was or was it just general line-cutting? What was your interaction with Dennis after that point? I'm also curious... Did you actually look up the word "act" for him?

PB: I don’t remember the scene, but it definitely was one of his bigger speeches that we trimmed. And yes, he actually had a dictionary out and we looked it up! At that point, we were taking one for the team. Dennis needed to vent, and not that he wasn’t right. It’s just that we were told by the producers that our job was to cut, and once Dennis had committed something to memory he didn’t want to do it again. And things were very stressful at that point. When we showed up it was about halfway through the shoot and it had been a long shoot under really difficult circumstances.

They had chosen to shoot in this abandoned cement factory where The Crow had been shot, and it was just not an ideal situation. It was not air-conditioned. It was 105 degrees. The sound was really bad, so I think they wound up having to loop a lot of dialogue just because the quality of the sound; it was really echoey.

It wasn’t a comfy studio, so people were more tense. When we were there I think the actors were really just kind of… Well, I know Samantha Mathis was working on another movie at the same time. So, she was really burnt out. She was doing that country western music movie with River Phoenix [The Thing Called Love] and I think they were an item at that time. So, she was shooting on that really late and staying up late partying and coming in and if you look at the movie-(starts laughing)-she looks like she’s sleep-walking through the movie.

Panoramic shot of the Ideal Cement Factory

RH: (laughs)

PB: She is, basically. And she’s a great actress, but, it’s just, you know, she was stretched too thin. So, like I said, the point I was trying to make is what the movie was was not ideal based on lots of things. Primarily, they didn’t have a script to begin with. And secondarily, the shooting conditions were really bad. That the editors were able to put anything together was to their immense credit.

RH: What was your interaction with other cast members, including Bob Hoskins and John Leguizamo? What were their reactions to the ever-changing script and shooting conditions?

PB: We were mostly locked away, so we didn’t get to interact much with the main stars, although we did learn that Bob Hoskins’ favorite whiskey is Old Pulteney. Fiona Shaw made a point of being nice to us, because she’s smart and was hoping to add more to her character: I think there were things she liked in Dick and Ian’s draft, which she mistakenly thought we were responsible for at first. We hung out with Fisher Stevens a bit; he was in our first movie, Mystery Date, and we got to know and really like Richard Edson.

As to the ever-changing script and shooting conditions, sure it wasn’t ideal and there was some grumbling, but everyone was still very professional. I think Rocky and Annabel’s strengths were more conceptual and visual, and with the script in flux and so much focus on the props and effects and such, it’s easy to imagine the actors feeling a little neglected.

RH: I do want to go back to the development of the scripts. From what we know, Barry Morrow wrote the very first draft, which was then followed by the Jennewein/Parker fantasy script and then you and Terry were brought in. How much information were you given from those earlier drafts and what were you told about them? Did you basically just latch onto what the directors wanted or-

PB: We were told, “Don’t even read these drafts, because we’re starting from scratch, coming up with a completely different take.” I think I skimmed [them] because I was curious, because Barry Morrow wrote Rain Man, so [I thought] “What did he do?” And I did [skim his draft], and it was pretty weirdly similar to Rain Man. So much so it had gotten nicknamed “Drain Man” in the production office.

So, I never actually got to read that script fully, but I understand there were some similarities: an existential road trip with two brothers, one cynical, the other a bit mentally impaired. And then all the Jennewein/Parker stuff, was like I said, you could see from the art department what they had done.

So, we were told to ignore that stuff and start from scratch. They bought us a Nintendo system to play, because neither Terry nor I nor the directors had been gamers, so we were playing Nintendo. And the directors, I don’t think were that worried about the Nintendo stuff, like the game references and things.

So, Terry and I sort of took it on: “Well, we’ve got to. There are people who love this game and they expect certain things out of the movie, so we can’t just ignore the fact that it’s based on the characters from this game.” But, at the same time, there’s not a story in the game, or if there is it’s the Jennewein/Parker story or whatever fantasy version you come up with; a sort of “Wizard of Oz” take.

Rocky and Annabel did Max Headroom, so they had that sort of post-apocalyptic sensibility and they were trying to do something much more hip. And Terry and I, our background is more as comedy writers, so we were thinking: “Okay: hip, a little dark… Parallel world… It’s Ghostbusters.”

So, our whole angle was to try to make it that tone of “Ghostbusters” and go for the unexpected. The directors and us both shared this love of “Whatever your expectation is, we want to subvert that.” So, we did a lot of things just to keep people on their toes and to keep people [thinking] “What! They did that?”

So, things like instead of mushrooms popping up [like] in the game, we created this fungus that’s destroying Dinohattan, and then we came up with a backstory that it’s the de-evolved King. In our draft it was King “Karma," just because it was “karma” that was destroying the city. I noticed on your site that one of the novelizations said it was King “Bowser.” I don’t know where that came from, unless it was in the Jennewein/Parker script or something like that.

So, like I said, we sat there [and] I played a lot of Super Mario Bros. and it’s very addicting. I was usually the one who was trying to figure out “Well, how are we going to do the coins coming out of something and how are we going to do Bob-Ombs…” It’s like, I wanted to have the references to the game, but in a way that was peripheral, like this is the reality and the Super Mario Bros. game created this weird fantasy version of that reality.

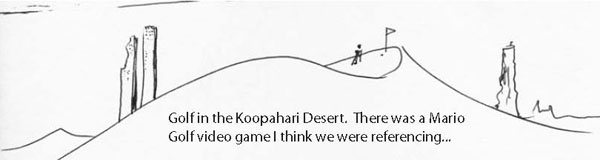

So, we did the stomper boots so they could jump from rooftop-to-rooftop and – you know – I think in one of [our] drafts they went off to play golf, because there was a Mario golf game at the time. (laughs)

Interviewer's note: The "Mario golf" game is NES Open Tournament Gold, released in 1991 for the NES. In an intriguing parallel to the film, this game takes place in the "real world," features Mario and Luigi as playable characters and includes Princess Toadstool and Princess Daisy as Mario and Luigi's caddies, respectively. This was the first Nintendo game to suggest a relationship between Luigi and Daisy.

So, there was a lot of stuff that was weirdly and very peripherally connected to the games. But, as I think I said somewhere else, Nintendo had nothing to do with anything. Like, they had no say in what happened in the story. And I think if they did that [the] movie probably couldn’t have gotten made. Certainly [not] this movie.

I do think you made a really good observation in that one of the big faults of the movie is the characters aren’t well established and you don’t really care about them and there’s not a relationship between Mario and Luigi that you get. They’re just so dissimilar. It was odd casting, and we were sort of at fault for the casting: we’d suggested John Leguizamo because we had seen him in Chicago doing his one-man show. And Bob Hoskins was… I don’t know how he got involved. I think our early choice was Bruno Kirby [because] we wanted the brothers to be kind of closer in age and fight more. There’d still be an older brother protecting the younger brother, but it wasn’t so much older and so the difference wasn’t so distinct.

RH: Right. Well, the more that we research the film the more apparent it becomes what they were attempting to do with it. You then realize that it’s really, really interesting to dissect and look at. How about you jump in Steven, I’m sure you’ve got some stuff to add.

SA: Well, Parker, you kind of stated that the game was more of a fantasy version of the film’s realistic take.

PB: Well, in the back of our heads that was the thought. Like, if Koopa were trying to create – you know, in his propaganda – the idealized version of his world as a game, it would be Super Mario Bros. That was sort of the backwards thought.

SA: I found that funny as I was actually attempting to understand the film’s concept and how it might relate to the games and came to realize that the video game is “The Wizard of Oz” and the movie is what “actually happened.” The different characters and references in the movie are a “And you were there, and you were there…” take on the events of the video game.

PB: Like I said, you look at the video game and there’s no story that you’re going to pull out to make a feature-length film. So, you just had to give that up and come up with a different thing. And that’s where Rocky and Annabel were so brilliant: they had come up with a way that made a story happen.

I don’t remember how the piece of meteorite thing happened. I’m pretty sure it’s something we worked on when we were sitting in the room for six weeks. But that gave us a lot. The plot mechanics. Like, “Okay: Koopa wants the piece of the meteorite to fuse the original meteorite that created the parallel dimension and if he can do that then the worlds reunite and he can take over and get all of our resources.” So, that’s an engine that can drive the story.

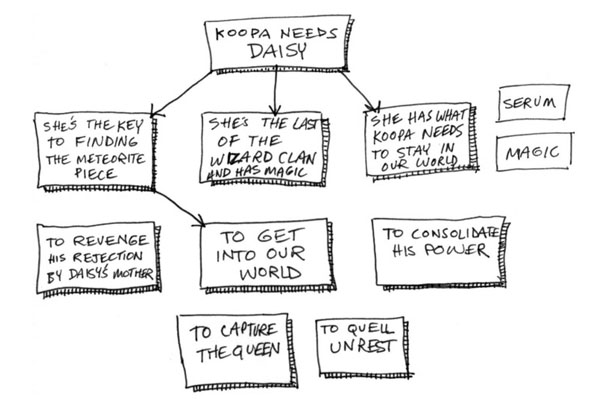

Why exactly does Koopa need the princess? Their guess is as good as anyone's

PB: And then, when we were writing it our goal was to show how the Mario Brothers become the Super Mario Brothers. So, we had to figure out what’s their trajectory of [characterization] and what’s their relationship. And what we decided is, “Okay, Mario has a big chip on his shoulder about being a plumber. He’s inherited his dad’s business [and] it’s not what he wants to do;” it’s sort of a “It’s A Wonderful Life” thing with Jimmy Stewart at the bank when he wants to be traveling the world.

[Mario’s] dad and mom died and then he’s forced to look after Luigi and so he’s stuck with all this responsibility that he never asked for. And in the end he learns through the adventure that he’s the greatest plumber in the world and he needs his brother and they’re a team together and that was sort of what we were trying to do for that. That certainly didn’t really happen in the movie, but that’s where we were coming from.

SA: Well, you played the video game. How did you and Terry approach adapting a video game into film? Rocky and Annabel's new vision for the film obviously required a lot of reworking of what the games established, so how did you and Terry try to reconcile their vision with what defined the games? What did you feel was "okay" to change and what wasn't?

PB: Oh, we were totally fine with changing anything.

(Parker steps away for a moment, then elaborates)

We weren’t even worried about the video game. We were worried about creating a story. The directors certainly weren’t worried about it. We thought “Well, let’s just – where we can – draw inferences from the game as best we can.”

There are archetypes in the game [where] you go “Okay, Toad is kind of the “helper guy,” so we’ll create our Toad and let’s make him part of the rebellion.” And, you know, there’s stuff that didn’t make [any sense], like [how] it’s Princess Daisy in some versions of the game and it’s Princess…

SA & RH (in tandem): Toadstool.

Interviewer’s note: Princess Daisy of the Super Mario Land side-series and Princess (Peach) Toadstool of the core series are two different characters, as has become clear in recent years due to their divergent personalities and appearances, but in 1992 there was some confusion over whether they were two princesses or one.

PB: -Toadstool, yes. Well, obviously we can’t name her “Princess Toadstool” in the movie; that would just be weird. (laughs) So, okay: “She’s Princess Daisy.”

[And] I think Koopa is a better name than Bowser. So, you know-You can’t make Bowser the bad guy. That’s like the ‘50s Sha Na Na guy [Jon “Bowzer” Bauman]. So, “Koopa” is a better “bad guy” name.

So, you just make those choices. And, in terms of the story, we just didn’t worry about it too much. It was just like: “We got this parallel dimension thing, we’re gonna make it work.”

RH: To cut in, were (or are you now) aware that the name "Bowser" is the current name of Mario's adversary? The earliest Mario games from while you were writing the script didn't mention the character's name, so for a while "King Koopa" or "The Koopa King" were how his character was known.

The fact that some of the novelizations and other sources call the de-evolved king "Bowser" is extremely confusing for younger fans of the game because "King Koopa" and "Bowser" are the same character. What's your take on that?

PB: You know, thinking back, I don’t think “Bowser” was ever really mentioned. “Koopa” was probably already established as the bad guy name in the earlier drafts.

SA: In retrospect, do you think that that kind of approach was really the best option considering how the fans of the games reacted to the film? Would you do it differently if you had known how they would react?

PB: Well. It’s so difficult to say. If we’d made the movie that was in our heads – our idealized version… Our script was the very first draft and obviously you don’t ever think you’re gonna go shoot a first draft. That was like “This is how much we got done on the movie.”

What we hoped to do was create – like I said – this “Ghostbusters” tone and it was supposed to be funny and adventurous and a little bit weird and out-there. If we created that movie – if we’d made “Ghostbusters” – and the fans loved it, it wouldn’t matter how much it diverged from the video game. Because a movie is different from a video game. It’s a completely different thing.

The problem was we made a crummy movie, so–(laughs)–I don’t think the fans were upset about how we differed from the video game. I think there was some curiosity, like “Well, what if… You made a movie that was more distinctly rooted in the feel of the video game.”

You know, the guy who created those games has a very distinctive view of things and an outlook, and even he’s not about the characters.

RH: Right! Exactly.

PB: The characters were created after the gameplay, so it’s not about that. But a movie has to be about the characters.

But, if you made a movie that was more in that “Wizard of Oz” sort of “game” world, I think you’d have a movie that skewed really young, that played to six-year-olds. And we were trying to make a movie that would hopefully play for an older audience.

But fans are curious: “What would that movie look like?” And it certainly wouldn’t have Bob Hoskins and John Leguizamo in it. (laughs) It’s like, “Okay, we got an English guy and a-(stumbles, thinking)-

SA: Colombian.

PB: Yeah, Colombian. (laughs) Yeah. And these guys are playing Italian-American plumbers. I don’t think anyone would have ever expected that.

SA: Well, it’s actually difficult to assess why people don’t like the film because the most vocal critics only offer the most nitpicky and trivial complaints due to their own misunderstandings.

RH: (understanding perfectly) Right.

SA: Like, “Why doesn’t Luigi have a mustache?!”

PB: (laughs)

Apparently, some people think this would've made the movie better.

SA: Why does it matter? Why isn’t characterization more important? So, it’s really hard to determine why people don’t like the movie, or if it’s not disliked at all as people are just following a mentality that it’s popular to not like it.

PB: Well, my own mother came up to me after the screening and said it was the worst movie she’d ever seen. So-(laughs)-it’s not a great movie. And I totally understand people’s criticisms of it. It’s not a movie that hangs together the way it should.

But, yeah. It’s like people who would go to, I don’t know… It’s like the Superman movies: I was always sort of like “Oh, they didn’t get Superman right!” But they did a lot right in the original Superman movies. But, you know, Superman doesn’t have wall-building vision. There’s like all sorts of weird stuff in those movies like “What!” You either have a suspension of disbelief and you’re into the story or you’re not, and in the case of Super Mario Bros. you’re just not pulled in. A lot of that is we made the movie in… ‘91, I think?

RH: Right. It came out in ‘93.

PB: ‘92, yeah. Anyway, back then computer effects were just starting to really be possible and they killed themselves to do like two or three computer-generated shots. You know, there was an extension of the scene of Dinohattan when you’re tilting up from the elevated train, and then there’s a pull-back from the World Trade Center buildings [Koopa’s Tower] where you see the Princess inside. And they pushed really hard to make those happen and they didn’t totally work. They needed to do like 50 more of those shots.

So, they never really got the world sold. You never really understood where you were in that world. It was just a big set and you never really got the feeling you were in this place, really. I think the effects didn’t help and I think the fractured nature of the story was not pulling you in as well. There’s a lot of things that are wrong with the movie. The fact that Luigi doesn’t have a mustache is really not the big problem-(starts laughing)-with that movie.

SA & RH: (laughs)

RH: Well, to me it’s like story in games then is vastly different from story in games now. Since Super Mario Bros. was the first attempt at making a film out of a game you had to take a game that had no story-that had only gameplay-and make a story out of it. I don't think the people that criticize the movie really understand that. It seems like all the negativity is stemmed firstly from the fact that it’s not a carbon-copy of the game. It’s because you can’t take a screenshot from the movie and it looks like it’s from the game. People that don’t like the movie seem to stem from that line of thought.

So, what I’m interested in is what you think attracted Morton and Jankel to the project. If they weren’t big Nintendo fans, were they interested in the property or did they want to just completely rework-

PB: You’d have to ask Rocky and Annabel. But I will say that they’re incredibly creative people. I mean, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who could sit in a room and just spin ideas the way Rocky can. They’re just like one after the other after the other. And that works really, really well in the world of 30-second commercials.

I think they were attracted to the project the same way the producers were attracted to the project. At that time it was really at the height of Super Mario Bros. In focus groups, you would learn that-whatever the metric is they used-more kids recognized Super Mario Bros. at that time than Mickey Mouse.

The game is like 25 years old now, so at that time it was at this peak of its popularity and it was this big phenomenon and these producers-The producers were a really strange set of producers for this property: you go “Okay, wait… The guy who directed The Killing Fields and The Mission wants to produce Super Mario Bros.? Roland Joffé?” And then his producer, Jake Eberts, is like this lion of the industry, this really well-established producer. He used to run this studio called Goldcrest, I think.

Well, they saw an opportunity because of the name-recognition: You know, “If we have a movie named ‘Super Mario Bros.’ we’re gonna get an audience for it. And then they went down the path of struggling to, well, “how do you do this? How do you make this?” I mean, the game is not story: it’s gameplay. And they went through a couple different iterations and it was not as easy as they thought. I think they thought they could do the thing that the fans are complaining they didn’t do, that they could make a fantasy movie that was in that world and, you know, maybe if you did it in animation it might work, but the way that they were trying to do it in live-action it really didn’t work.

So, what attracted Rocky and Annabel? I think they saw that it could be a huge thing. I think that they might have had this “parallel dimension” thing as a story that they were interested in even before they adapted it for Super Mario Bros. That might have been something they could have come up with in the course of generating story ideas for themselves. I don’t know. You’d have to ask them. (laughs)

RH: Right.

PB: They definitely saw an opportunity to do something that had a cultural hook. Because they had done Max Headroom and that was a big pop cultural thing in the ‘80s. And they were looking to make another splash like that, I think.

I will say, what I was sort of getting to before, was that we sat in a room for six weeks and these guys are incredibly creative, but they had sort of developed a “thirty-second mindset”. So, the ideas that you sort of thought you agreed on the day before, the next day were the old ideas. And they wanted the new ideas. (laughs) They wanted the “new” new, Rocky would always say.

So, a lot of the frustration for Terry and me was just trying to get them to agree and settle on “What is the story going to be?” We did a lot of, you know, a lot of ideas. [We] threw a lot of stuff on the wall. And, ultimately (and probably to our detriment), Terry and I decided “We’re gonna have to just go off and take what we’ve got and try to do the best we can to concoct something, so we’ve got it on paper; otherwise, we’re just going to keep sitting in this room and keep coming up with new ideas and we’re never going to get a script written.”

So, we finally did that and while we were doing that I think they were unhappy with just the process and I think they brought in a friend of theirs – a guy named George Stone – to knock around even more ideas and I don’t think the producers were happy necessarily about that. I think everybody just wanted to get the thing moving forward, because they had – I think – a release date set in stone. I think they were shooting for the Memorial Day-release, big summer movie thing.

Interviewer's note: George Stone was a co-creator of Max Headroom.

PB: So, the producers were looking at the time we were spending in the room spinning ideas and going “You know what, the script has to get written. We’ve got to get sets built. We’ve got to get a cast hired.” By us going off alone, I think that sort of sealed it in terms of us continuing on the project. We no longer had that sort of daily interaction with the directors and I think they had, in their heads, kind of moved forward in a different way around the story.

We turned in a first draft [and] we did a little bit of rewriting. I think I showed you like the first seven or eight pages. It was the first thing we turned in and we immediately realized what our mistake was: I think in our first, first draft Daisy and Luigi were already boyfriend-and-girlfriend, and that’s not very dramatic.

So, we wanted to rewrite that and make Luigi meet Daisy in the first few pages and I think at that time an offer was out to Bob Hoskins, so some of the characterizations we had for Mario just weren’t going to work.

[In our first pass,] he was more Bill Murryesque… He had a chip on his shoulder, but he was also scamming on girls and he had-(laughs)-a younger personality than Bob Hoskins, lets say that.

Interviewer's note: You can check out that "Bill Murrayesque" draft HERE

So, we rewrote it, addressing that and other notes from the producers and from the directors, and pretty much the minute we turned in our revised draft, like the next day, Fred Caruso, the line producer who’s a really sweet guy, he came in and, in the nicest possible way, said, “Hypothetically, how soon could you guys get packed up and get out of this office?” (laughs)

RH: Oh man.

PB: It’s like “Oh, okay.” We were done. So, we thought “Okay, well that’s it. We’ll enjoy the movie with everyone else and see how they did.”

RH: Taking that thread back to the very beginning of your involvement with the film, how did you and Terry first find out about the project? Were other writing teams pitching stories, or was it just you and Terry?

PB: Oh. So long ago… You know, the agents get word of open jobs, and try to get us in to pitch. It had been a while since we’d scored a gig, and we got shuffled to a younger agent, Bayard Maybank. So, we really have him to thank-slash-blame. We’d made the mistake of thinking we could sustain a career and still live in Chicago like our friend Tim Kazurinsky. Or John Hughes or Harold Ramis. But, of course, we weren’t those guys.

SA: On that same topic I also wanted to briefly go back and discuss your initial pitch, if that’s okay.

PB: Sure. Well, like I said, it’s almost immaterial, because the reason I think they hired us was because I did the drawing of the pipes that go down into the evil-looking eyes. My “ad-guy” went to work and I made the movie poster that I had in my head. Our rapport with the directors and that drawing was pretty much why we got the job.

I can’t remember anything that would have stuck from that pitch – I mean, you read it, [but] I haven’t read it recently – other than the throughline we wanted, which was “How did the Mario brothers become the Super Mario Bros.?” That was the obvious question of the movie.

SA: Well, it’s kind of an interesting mid-point between Jim and Tom’s early fantasy-based script and your later science-fiction-oriented script. It’s almost feels as if their original script was re-tailored to fit into Rocky and Annabel’s “alternate dimension” vision, so how did it originally retain all those fantasy elements and how did it become purely science-fiction?

PB: Well, all I can tell you is we didn’t read their script, but there are certain elements of the game that [just stick out that you would keep]: you’ve got a bad guy named Koopa, you’ve got a princess that needs rescuing, you’ve got Yoshi, you’ve got Toad… There’s certain elements that all the writers kept. Since I don’t really know the structure of how their script worked, I can only assume. The producers certainly knew their script and they may have pushed for certain elements with Rocky and Annabel, I don’t know.

Let me say this: It was twenty years ago, so I’m not totally sure if I remember this correctly, but, when we were writing, we turned in like thirty pages at a time, so we turned in the first act and then we’d go work on the second act and we’d turn that in. Because everybody was so pressed for time they wanted to get us notes and see what we were doing as we were doing it.

That’s a really bad way to work, because people get excited and they get attached to things and then you wind up going, “Okay, well that’s not working,” because everything you set up in the first act, that’s where you have to set everything up that you’re gonna pay off. So, if you’re writing the third act and you go “Oh shoot, we want to pay this off,” then you’ve got to go back to the first act and change it. And the producers were like “We want to keep…”

In fact, I think they may have even wanted to keep the first act of the Parker and Jennewein script. Like, they thought we could just start from what they did. Their interest is to get the thing moving forward and get what they paid for-you know, they paid for a draft. They want to get as much out of it as they can. And I think we at one point had to convince them to go back and change some of the stuff we wrote, because they wanted us to keep just moving forward. It was a weird process. I’ll just say that.

RH: Obviously going from a fantasy version with a completely different script and director and team and completely switching to what you, Terry, Rocky and Annabel did must have been a daunting task. Do you think if the producers had gone with Rocky and Annabel’s vision from the start and stuck with you and Terry that you would have had more time to really flesh out the story and would have been able to come up with a more cohesive plan than what ended up on film?

PB: Um. (thinks) That’s a tricky question.

RH: (laughs)

PB: I certainly think that you can’t get an ideal script from going through multiple writers and hiring a guy to do the shooting draft in 10 days. (laughs) You just can’t get a decent script that way. At the same time, the way Rocky and Annabel worked was kind of exhausting. I mean, it was just a lot of… (thinks)

RH: (suggests) Iterations?

PB: -a lot of iterations. A lot of ideas. It was hard to kind of shoehorn everything in. We needed to be stronger writers; I think maybe more seasoned writers who could sort of say “You know what: No… That’s not going to work.” (laughs)

Or, “Let’s stick to this throughline. This is what the movie’s about. Let’s thematically stay on this path.” And we just weren’t experienced enough to really do that. And I think that’s why they went to Dick and Ian, who were veteran guys. I think the producers probably thought “These guys are veterans. They can whip the script into submission and get Rocky and Annabel on board.” I think that was the theory. Since I didn’t read their draft, I don’t know how far that theory went.

But, I would say that we could have made it better, [but] I don’t think we could have made a great movie the way we were going because we were really enamored with the directors and we didn’t do our job as writers to put our foot down and say “What is the story about? Who are these characters? What is their journey?” You know, it’s not just about the cool stuff we’re making, because that’s what they were interested in. The directors wanted to do cool stuff and make-

RH: They were graphics pioneers.

PB: –a hit and do really outlandish stuff, yeah. And they were interested in the way it looked and as writers it’s your job to make the story work. And I’d have to say Terry and I: we made it funny and we made a story work, but I don’t think we nailed it. I don’t think we ever had the real–

You know, one of the first things you want to do with a movie (and over a long experience you’ll learn this), it’s like: Okay, you really just have to decide: What is the story about? What is this about? Why am I doing this? What’s the theme of this story? And then you really have to be disciplined and make the movie that’s about that and make every scene a reflection of that, and certainly Super Mario Bros. had nothing going in that department.

But, you know, on the same side: Ghostbusters doesn’t really either. We were trying to make “Ghostbusters” and we thought “Okay, if we make it funny and hip and the characters are likeable enough [and] the monsters are cool, it’ll be good.” So, it’s just a process.

RH: Yeah. In contrast to what was actually filmed, the opening of your original draft took the right amount of time to set everything up. All of the characters – Daisy in particular – are introduced better than how they are in the movie.

SA: Yeah, definitely.

PB: Well, thanks! It would have been nice to see that part.

(pause)

Yeah, I think there’s an inherent flaw in the movie-making process, which is that the way the Writer’s Guild has set things up, only so many people can get credit for a movie. The way deals are set-up when you get sole credit for a movie you get a lot more money [and] when you get shared credit you get more money. Every writer who comes in has a vested interest in making the movie-not even just from the financial point, from an ego point-everybody has a vested interest in making it their movie.

So, any movie that goes through ten writers-(laughs)-is just gonna lose a cohesive throughline and people aren’t going to go “Well, this worked perfectly well in this previous draft. Let’s keep that.” Everybody has an incentive at some point to just ditch everything that came before.

So, yeah, I think our set-up was pretty good, but the writers who came after didn’t have any incentive to keep it. So, they usually just sort of randomly make changes. I really wish the Writer’s Guild or somebody would step up and say “You know what we should have is some sort of-Okay, let’s say two writers or two writing teams get the credit for a movie… Why isn’t there a credit for everyone who worked on a draft?”

Even a draft that doesn’t work, you learn something valuable. So, there could be like a “creative contributions by” and then list everybody who ever touched the thing, because they should get credit. I mean, certainly as much as the makeup assistant gets a credit. I don’t know what George Stone did on his draft, but whatever he did it was something that they figured out they didn’t want to do for the movie. So, in some ways it’s valuable.

RH: It’s interesting to pick out those kinds of things because you’re right. You don’t know this stuff, so Steven and I have had to really dig deep to find everything out. Like, the only reason we initially knew about the whole Barry Morrow script-you telling us was a huge help-was because there’s books and interviews and promotional stuff from when the movie was made and they’ll say stuff like “The producers hired Barry Morrow to flesh out the characters,” and this and that, but they don’t say “And then the producers hated Barry Morrow’s draft and threw it out!”

PB: (laughs)

RH: It doesn’t say that stuff!

PB: The reason Barry Morrow got the gig is he was an A-list writer they wanted to use to get money and attract attention to the project and get acting talent involved, and, you know, you go “Oh, Barry Morrow’s involved. It’s probably going to be pretty good.” And for all I know that movie could have been really interesting, but it wasn’t going to be Super Mario Bros. It was gonna be even less recognizable as Super Mario Bros. than our movie was [compared to] the game.

So, yeah; Barry was the first guy they hired and they continued to use his name in publicity and stuff because I think they wanted to have that credibility attached to the project. And they financed the movie themselves. This wasn’t a studio-financed movie.

So, Lightmotive came up with-Jake Eberts and those guys found the money. I don’t know where they found the money-(laughs)-and I’m sure the people who gave them the money aren’t too happy about it. But, they thought “Let’s leverage the situation. We’ve got this great property: We’re gonna make the movie and then we’ll be able to sell it and make a lot more money than going in and partnering with the studio. We’d have to give up a lot of that profit participation and stuff.”

(pause)

(laughs) You know, it’s funny because you guys are sort of looking at this sort of like an archeological dig-

RH: (laughs) That’s exactly what Jim and Tom (original "fantasy" screenwriters) said! That’s interesting…

SA: Wow. Yeah.

PB: You know, these little pieces here-and-there and trying to piece together this idea… And I will tell you that there’s no-You know, it’s probably how we looked at the dinosaurs. We look at these fossils of dinosaurs, and, from what I understand, like scientifically, just the notion of something getting fossilized: it’s not a really common occurrence.

So, our picture of the dinosaur world is really limited, because the evidence that we have left behind after millions of years is scant. So, things could have been radically different than what we’ve imagined. We can put together this sort of throughline in our heads about what happened, but usually the truth is much different. And in your case, the throughline you’re putting through your heads is that there’s a throughline. I think the process was really fragmented and only marginally did anybody’s script really impact anybody else’s.

The people that had the most sway over what happened in this movie, creatively, were the directors. They were the guys who really came up with the concept. It was their job to shepherd the script and get it to where they wanted it. They fought with the producers and there were things that they didn’t get that they wanted and, you know, nobody got what they wanted. If there are similarities between the Parker/Jennewein script and ours…

You know, who knows why? (laughs) It’s not because anybody consciously grabbed stuff from their script. It’s because there are elements of the video game that just naturally come about. And pretty much anybody could have come up with a lot of the story. If you’re gonna say “parallel dinosaur world in Manhattan” and just the directors coming in with their take and Koopa was already named as the bad guy, I think, from previous drafts and maybe Daisy was already named as the Princess in previous drafts. Who knows. I don’t remember how Toad got involved in our draft, but it could easily have been Toad was the “helper character” in Jennewein/Parker’s draft and so we just, you know- Our “helper character” got named Toad. I mean, who knows.

Parker on set, after being re-hired for rewrites

But, it’s not like there was a path from one thing to the other, other than [that] each writer who came on-board wanted to make the story work and each writer, or writing team, tried the best they could to get a draft done that would make the story work. And whatever elements were floating around… They became more and more constricted because the art department had to get to work and certain things started shaping into- Basically from the start of our draft: you needed Goombas, you needed the tower, you needed the place where the meteorite was.

So, you know, there were certain things that had just started to gel. But it’s not like the pieces fall together easily, like “Well this is obviously this part is from here…” It is what it is. And it’s each writer trying to make their mark and do the best they can.

(pause)

I have a huge amount of respect for Ed Solomon. I think he’s brilliant, he’s hilarious. It’s super-human to write a shooting script in ten days, so he killed himself to make that happen and probably burned himself out and then disappeared. (laughs)

But I also think Jennewein and Parker are really funny and brilliant. I didn’t read their script, but I’m sure they did a great job too. It’s just the directors were the guys who ultimately had the final say and if the movie isn’t working you really have to go “Well, you know what, they just didn’t pull it off.” The directors are the ones in this case. A lot of the times it’s a writer or a writer/director and you can say “Okay, that’s the genesis of that story. The writer really had a draft and the director didn’t deliver on the draft.”

In Super Mario Bros.’ case, there was never a script. It was always the script at the time they were shooting. So, like I said, we came back and we wrote probably 20 some-odd, 30 pages of new material when we came on set. We rewrote how Daisy and Luigi meet, we added an ending scene for them, we shortened stuff… We did a lot of stuff while we were there.

If anything, I think the directors thought we were too “gaggy”. Our “Ghostbusters” sort of sensibilities wasn’t necessarily in line with their sense of humor, [which] was maybe more British. (laughs) And I think they were shooting for a lot “drier” than we were. We were going for the gags a lot more.

RH: Do you recall why you and Terry were tasked with reworking how the Mario Brothers meet Daisy? According to both the ADR notes you provided and other sources (such as screenshots) it seems like both of these totally different "meeting" scenarios were filmed.

PB: Well, it sounds like they weren’t happy with how it came out when shot, and since they were reshooting, they probably asked us to address whatever they weren’t happy with. I really don’t recall, sorry.

RH: So, were there other bigger or different ideas that were thrown around with Rocky and Annabel that you would have worked into the script but, for whatever reason, didn’t make it into the movie at the end of the day?

PB: Well, I mean there were ideas… That didn’t make it into the movie?

RH: Yeah, I should have explained more.

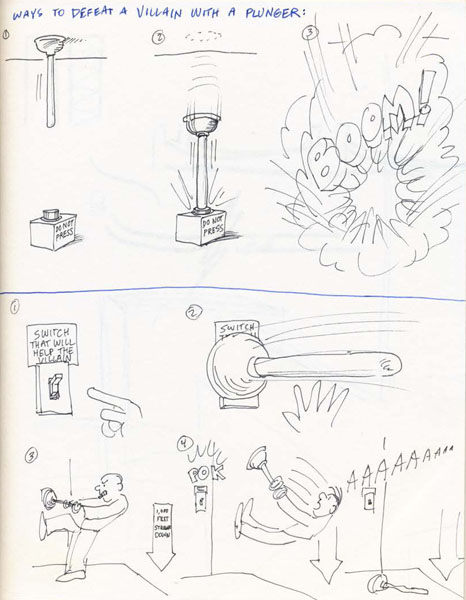

PB: Yeah. I started reading our script and I kind of couldn’t make it through it, so-(laughs). I got about two-thirds of the way through. And I don’t totally remember how our script ended, but I remember we’d come up with a bit that we’d planted where Mario could throw plungers up on the ceiling and he knew how long they would take to fall down and he would-

RH: Yeah, I really liked that.

PB: –time them and sort of have this–(laughs)–instinctive thing and then we had that sort of Robin Hood shot of the plunger coming down off the ceiling in the meteorite chamber and hitting something at the right time. I will say that when we came to the set and we read the ending that was [them going] back to Manhattan and this… I don’t remember us doing monkeys and stuff. But maybe we did. I don’t remember.

How to suceed in being a heroic plumber without really trying

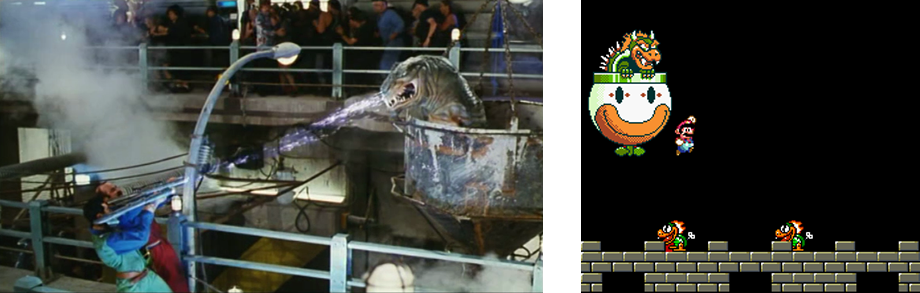

PB: I think the ending–(laughs)–the ending needs a lot more work than anybody ever got to do on it. And, in fact, the ending where Koopa comes out of the bucket and he’s a dinosaur head? Nobody had an idea that was gonna happen until we were on the set. Terry and I pitched that and the storyboard guys came up with a version of it and it was sort of “Well… We know we need to heighten things at this point; this is the best we’ve got right now that we can do with no money.”

RH: Why was it necessary for you and Terry to come up with that idea on the fly? Was the original climax of the film too expensive to accomplish? What was planned before you had to write that new climax? Also, like the Super Mario Bros. 3 parallel with the transforming king, a lot of people have pointed out that Koopa standing in that “bucket” is reminiscent of the final battle with Koopa in Super Mario World. Was that an intentional reference, or just another interesting coincidence?

PB: Oh, I’m pretty sure that was intentional.

Coincidence? I think not.

PB: But that was never in the script when they went to go shoot the thing. So, all that stuff came later.

So, I would say there were lots of ideas, but ultimately, every idea, every great idea doesn’t matter; it’s what you get on the set, and you built this thing, and you have these-(laughs)-characters and you have these actors and everybody’s exhausted and what can you get in the can, you know, on film to make the movie happen and usually it’s not the great ideas that you had thought about a year ago in a room.

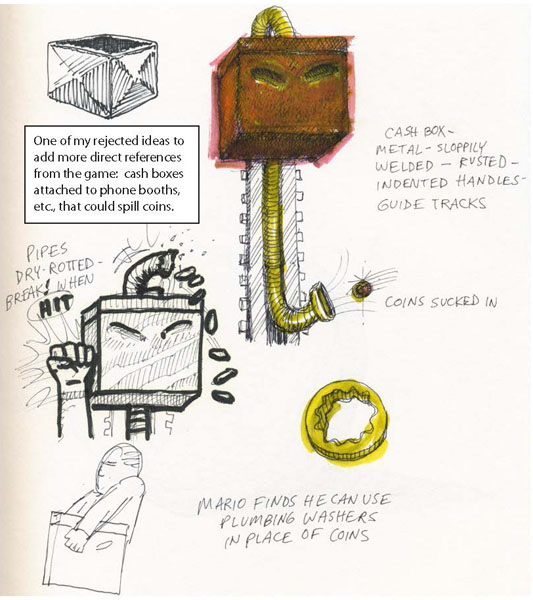

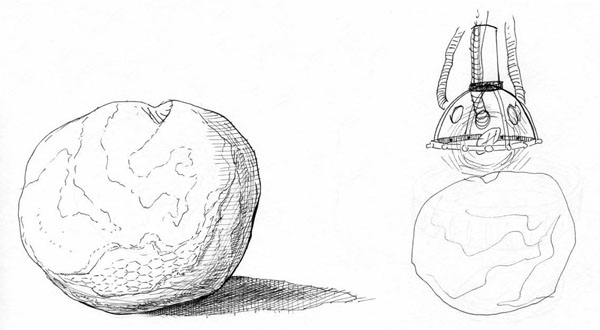

I will say, looking at my old notebooks, I was a lot more the guy trying to literally take game elements and get them into the movie. I had coin boxes over the phone booths that delivered Koopa Coins and I had drawn all these things that were basically ways to take the stuff from the game and get it into the movie. And the directors were just never that worried about it. (laughs)

These would've been really cool to see on film

PB: So, all that work from my end was sort of for naught. I have a lot of sketches of cool things that were sort of a weird amalgam of things from the game that I sort of translated into the world of the movie and a lot of those are in our draft, but ultimately [some] didn’t wind up making the cut.

RH: Well, the cool thing is a lot of those big concepts that you’re talking about-the ones that did make it into the movie-are, in my opinion, the more intriguing parts of the movie; like turning the fungus into something taking over the city. I would have definitely liked to see a lot more of those things interpreted into that kind of world that Rocky and Annabel wanted to make. I think both of those things working in-tandem were really nice.

PB: That has a really weird vibe to it. (laughs) The way it turned out was a lot more gross than what– (laughs)–I had in my mind. It was just really disgusting with the sort of methylcellulose fibers of the stretchy-stringy stuff. It’s like “Aouhh. That’s really gross!”

Like when Daisy has to talk to her father and he’s a de-evolved fungus head. It’s like: “Wow, that is weird… That is seriously trippy.” I think that kind of stuff may be what really turns off the fans. I mean, that is so not the game. It was Rocky and Annabel’s world.

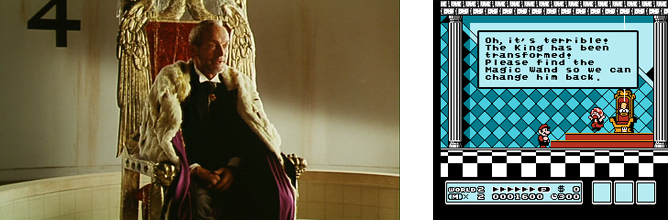

RH: You know, me and Steven keep picking apart these things and trying to find connections between the movie and the games and have found The King really interesting because the plot of Super Mario Bros. 3 is Koopa turning the kings of different lands into different creatures and the Mario Bros. have to change them back.

PB: I don’t remember if Super Mario Bros. 3 was out when we were playing the game. I know mostly we played Super Mario Bros. 2. Yeah. It’s an interesting parallel. I can’t say that fact had any bearing on the King turning into a mushroom [because] I’m pretty sure that came from Rocky and Annabel. I think Rocky came up with the idea that it was the de-evolved king. It’s sort of my vague memory of that event. But I could totally be wrong. I know Rocky wasn’t that into the game, so I don’t think he would have keyed on something from Super Mario Bros. 3 and went “Let’s turn that into something in the movie.”

A king transformed is nothing odd if you've played Super Mario Bros. 3

PB: I can tell you, Rocky and Annabel were not interested in worrying about anything in the game and how to turn that into anything in the movie. That was totally what we tried to add when we were making the story happen. And I think other writers, too. I think everybody who took on the script sort of had it in the back of their minds, “We can’t just ignore the fact that it’s based on this video game. We have to keep elements from the video game that make sense and the fans are gonna be expecting something that has a tie-in to the video game.” (pause) What I always wanted to do was have it be sort of a “wink-and-a-nod” to fans. Like, when in our draft when you meet the Mario Bros. their truck is parked outside and the logo of Super Mario is on the truck.

RH: We would have loved that.

PB: So, we wanted to have these things that [would make the sort of people who knew the games go] “Oh! That’s what they’re doing. That’s funny.” So we had a lot of in-jokes: I think we had a newspaper vendor sort of watching TV-a sort of social commentary joke- Like, the guy at a newspaper stand who’s watching TV and then he’s looking down on some 12-year-old who’s playing a handheld video game and going “Gosh. Kids today.” (laughs)

RH: I mean, yeah. That reference right there- I mean, me and Steven both kind of focused in on that. Like, when we read that scene that you’re talking about we found that it really provided an inherent clash and reconciliation between the real-world video game culture and the fictional world you were trying to get into your story. It was a thematic contrast like the kid that’s reading comic books in Watchmen.

PB: Right, right.

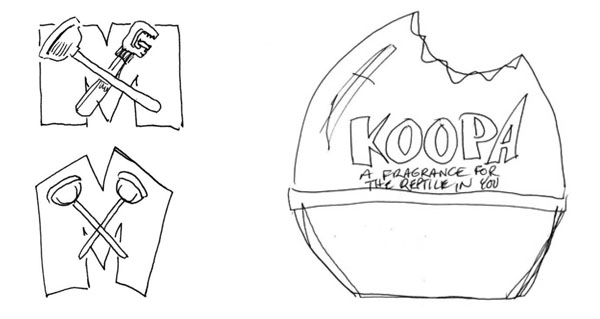

Look at these early logo concepts and a Watchmen-esque Koopa perfume

RH: Was that intentional?

PB: Oh totally. One of the things I always worry about when I start a script is “How do I set-up the audience’s expectations for the movie?” When you set-up the movie, you’re leading the audience to expect certain things: what kind of tone, how funny is it gonna be, how dark…

So, we really worked on that opening sequence to try to say, “Okay, this is not your father’s video game.” It’s not your father’s Oldsmobile. It’s not what you’re going to expect for Super Mario Bros. and sort of acknowledge that. And so we were trying to do that in a playful way and, you know, it’s subtle, but we were very aware of “What are we setting up initially.” And that’s why we were so flummoxed at the very end of the process. The producers had had screenings and people were still confused, so they wanted to add this prologue-

RH: (laughs knowingly)

SA: Oh god…

Interviewer’s note: Even the movie’s fans agree that the animated intro isn’t good. It’s just terrible.

PB: To explain the dinosaurs, the whole thing. And it was like, “Really? You think that’s going to make it better?” (laughs) And Terry and I wrote a few tests we thought were maybe funny, and I think I sent those to you, but [we thought] “This is a bad idea” and even if they executed it well, it was [still] gonna be a bad idea, and they executed it really badly.

The animation was supposed to be reminiscent of the video game and that was never achieved. (laughs) So-(laughs again)-it just sets you up for the worst movie possible, that opening. And, unfortunately, then it kind of delivers on it. (laughs)

"Y'know, it just don't get no better than this." Actually--it could've been a lot better.

RH: I mean, at the very least, the dinosaurs in that animated intro could have looked like the characters from a Mario game. I mean, that would have made a tad more sense.

PB: Yeah! Yeah, I know! I don’t know what they were thinking… I don’t think they knew what they were thinking at that point. They were just panicked because they had screenings, the movie wasn’t tracking the way they’d hoped, and these were sort of Hail Mary passes at the end. “People are gonna be frustrated if they don’t understand what’s going on, so let’s just spell it out, initially.” And, like I said, that’s not setting-up the audience’s expectations in any way that we were hoping for.

SA: Speaking of poor attempts at humor: What’s the deal with the running “joke” of Koopa ordering pizza? According to the ADR document you sent us it was even taken as far as filming the pizza boy gloating over the defeated Koopa after his demise. Do you know how and why that made it into the movie?

PB: I’ve honestly blocked that out of my mind. It doesn’t sound like our joke. I have no idea where that came from, other than Koopa was supposed to be a character of huge appetites. (pause) Anything else?

RH: You mentioned that you and Terry played Super Mario Bros. 2 the most. The villain of that game is an evil frog named Wart rather than the usual King Koopa. Were you guys aware of that? Although the name "Wart" doesn't appear in your draft, a character by that name does show up in subsequent scripts for a character that was ultimately cut down to a non-speaking role.

PB: I think maybe someone in the production office had compiled an overview of the Mario Bros. world and characters, kind of a cheat sheet. We didn’t want to draw from just one game, but more overall. I don’t know how “Wart” showed up. Maybe Ed Solomon.

SA: While Super Mario Bros. 2 seems to have influenced you two the most there’s also some indication that the other games affected your writing. A lot of people are surprised that Yoshi from the then recent Super Mario World made it in at all, so you must have played that game enough for it to leave an impression.

PB: Yoshi fit perfectly because of the dinosaur theme, and he’s memorable in the game, unlike “Wart.” Like I said, I’m fairly sure someone had compiled all the characters from the various games into one “cheat sheet,” which we would go back to. He might have gotten special attention because of the newness of the game.

SA: Super Mario World was also set in a place called “Dinosaur Land.” Other than Yoshi, that game introduced other dinosaur-creatures, including Dino Rhino, Dino-Torch, Rex and Reznor. Did Dinosaur Land factor into how you and Terry wrote Dinohattan and the parallel world in any way? Why didn’t we see more explicit references to these creatures considering how well they would have fit into the film’s concept? Could that game have factored into substantiating Rocky and Annabel’s vision for the setting?

PB: You’d have to ask Rocky and Annabel, but we never got a chance to play Super Mario World at the time. If we had, we probably would have tried to work more of that stuff in.

SA: On a broader level, how closely did you and Terry work with Rocky and Annabel on creating the backstory for the alternate world and its characters? Is there more to the foundation and history of that world and its characters that isn’t seen in the actual script. How much world-building did you put into it?

PB: We did a lot of that, but-(sighs)-You know, we sat in a room for a month-and-a-half with Rocky and Annabel and worked on this world. There are a lot of iterations [and] a lot of different sort of tangents that we went on. It was a long time ago, so all I can tell you is that, like I said, Rocky and Annabel had a tendency to dismiss the ideas we sort of agreed on the day before. (laughs)

So, we wound up never having the kind of cohesive understanding of that world that you would have hoped to get, that I think you’re asking about. So, there are not more ideas about the world of the movie that didn’t make it into the film. I think we all thought it was gonna be cooler. (laughs) You know, the de-evolution thing. (laughs)

SA: How did that come about, the whole de-evolution concept?

PB: Well, it just made total sense because of the storyline. The storyline is the people in this other world evolved from dinosaurs. Because we had that as a theme, it just made sense that-Koopa is accessing his sort of reptilian side to do this. He wants to take over the world and he has this more reptilian brain.

So, it made sense, “Okay, his thing is getting people back to their roots to be this army.” I think we initially had this idea, you know, the Goombas are soldiers. They’re the perfect soldiers. They’re killer reptiles [that] only think about eating and killing. But the outcome was unexpected for him, because everybody had a little bit of a different personality or different DNA. You know, Toad’s DNA has got toad in him. (laughs)

So, I think we had a lot more ideas in that whole realm and the way it got translated into the final movie was just kind of goofy. I think we had a more “science-fictiony” take on that.

But, like I said, Terry and I were often going for the jokes, so it just seemed like “All right, well let’s go for the joke on that. It’s funny.” [Koopa] de-evolves people so they’re stupid and he can use them. So, and again, the special-effects were not great. The whole de-evolving thing was kind of… not that great. That made it goofier.

SA: Actually, in your initial draft Toad reveals that he’s “part chameleon” and demonstrates that trait several times throughout the story, so are you just misremembering, or is there something more to this?

PB: Wow, I’d completely forgotten that. Yeah, that was going to be a whole thing, Toad’s ability to blend in. Like, you’d be looking at the wall and it would blink and [then] Toad would step out. He’d be painted to match. That’s a good example of the way-too-many-ideas we were dealing with.

RH: While we're on the ancestry of Toad I’d like to ask if there were specific dinosaurs or reptiles in mind for the other characters, such as Daisy and the King, or Iggy and Spike?

PB: Not that I recall, though Spike would come from something spiny and Daisy has such a great connection to Yoshi there’s probably some connection there.

SA: I also want to quickly say that the practical effects were amazing, though you’re right in that the digital-effects were completely underutilized.

PB: I would agree with you 100%. The guys who did the Goombas and Yoshi- Those guys on set were unbelievably talented. They were walking around with that Yoshi puppet and it looked absolutely real. Like, it was just unbelievable they could do that with a rod-puppet. And the Goombas were brilliantly designed, it was just like “Oh my God! That’s brilliant!” And they took a lot of work to run. The guys inside the suits were killing themselves to make that happen. They couldn’t see a thing.

I think the guy who supervised all the digital special-effects, a guy named Chris Woods, [had] made the decision, and it was sort of a cost thing where he argued that he could create an in-house effects team to do the digital effects for cheaper than we could go out and get the effects done by ILM or something. And, it’s one of those “Yeah, well, you can… and you get what you pay for!” (laughs) And I think he may have been in over his head a little bit on that. I don’t know.

From left to right: Koopa the Sportsman, Terry Runté, Parker Bennett, and Chris Woods

SA: Well, this is somewhat related to the special effects, but was it ever discussed why the parallel-world dinosaurs had evolved into humans? Is there an explanation for that, or should we just suspend disbelief for the sake of the story?

PB: Well, it’s because in our world the dinosaurs were wiped out and in the parallel dimension the dinosaurs continued [to evolve]. Because we’re not making a digital [film] – we’re not making Avatar – they had to evolve into something that human actors could play, so they became human. (laughs)

You just didn’t have a choice; of course they became human. So Dennis Hopper could play [Koopa].

SA: Well, in that regard, would you say that they actually are human-looking, or should we just assume they look more like reptiles? Visually, of course they’re human-looking because they’re played by human actors, but is that literally how they look in the world or should we just assume that they have more reptilian qualities such as cold-blood, scales, etc.?

RH: Reptilian tendencies.

SA: Right.

PB: I think our hope was that – sorry, this was a long time ago – in our mind they had evolved into- [Parker steps away for a moment]

[continues] –The simple answer is: they were human. They evolved – essentially – into whatever form of human that can evolve from the reptilian side, as whatever form of human can evolve from the primate side [like] we did. In the back of my mind I think there were more ideas about Koopa messing around with de-evolution technology; that the people in their world had various degrees of stability in terms of being human.

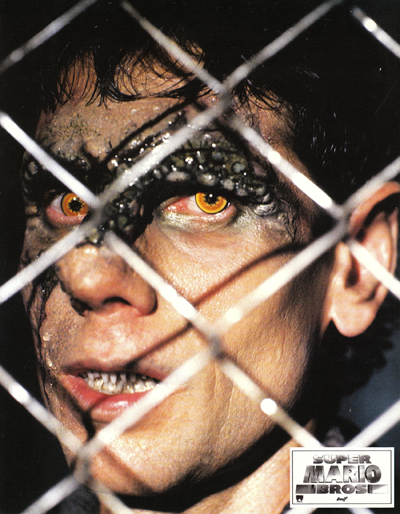

"The people in their world had various degrees of stability in terms of being human"

PB: You know, I think there’s a scene where [Koopa’s] lizard tongue comes out and his eyes turn to slits and he’s kinda losing it. He’s trying to access that more lizard-brain, primal-power thing and he’s experimenting on people and doing all this stuff and I think in our world-in some version of our world there were gonna be weird forms of different creatures that would have even more parallels to the video game because of his messing around with the genetics.

"He’s trying to access that more lizard-brain, primal-power thing"

PB: So, we had that possibility that we could explore more kinds of creatures in that world, but it never happened. I think things needed to get simpler, not more complicated. And, budget-wise, it was not gonna happen.

I think we had nods to things, like you had Toad with his spiral haircut. We tried to do it in the costume-design instead of in prosthetics. So, there was Bertha [with] her big red rubber spiked suit (the bouncer at the club) and stuff like that.

SA: If the production had had more money to put into prosthetics and makeup, or even CGI, what sort of different creatures from the games do you think you and Terry would have tried to work in?

PB: I think it might have been fun to have Koopa and his scientists creating more weird hybrid tech creatures: walking Bob-Ombs, that sort of thing. Rocky and Annabel made things a lot more “organic” than what was in my mind. I was thinking more Bond-villain lair.

RH: Speaking of costumes, could you speak on how Mario and Luigi's red and green "game outfits" were implemented into the film? Many fans (myself included) consider the scene in which the Mario Brothers get their suits as one of the best.

I recall the early script had the Marios wearing their overalls throughout the entire story and I have heard somewhere that Rocky and Annabel were opposed to having them wear the game costumes, but I loved the way they were finally incorporated. Were you and Terry involved in making that transition, or was it done later?

PB: Well, the “suiting up” was definitely in our draft, but it’s most likely the costume designer who pushed the red and green overalls. I think we just assumed.

RH: Getting back to the “reptile brain” discussion, my question is, at this point, Daisy in the film is considered to have evolved from dinosaurs… The one weird thing I’ve noticed is that Daisy didn’t show more dinosaur-like tendencies. Koopa, for example, would hold his hands up like a T-rex while Iggy and Spike acted like predators on the hunt.

So, were Daisy’s reptilian roots not explored further in the film to make her relationship with Luigi not so strange, or was there something else in play? Todd Strasser’s monetization kind of hinted that Daisy’s mother might have been a human from our world rather than a dinosaur-human. What was going on with that?

PB: Well, I don’t know how Daisy’s mother could be a human being from our world because she wouldn’t have laid an egg.

RH: Riiight.

PB: So, I don’t know what the writer [was getting at.] You know, the guys who do those novelizations: they have a hard job because they usually get some sort of early, incomplete draft. They have to start working on it before the movie’s done. (laughs)

It’s really interesting when you read novelizations because you often find stuff that was either cut out of the movie or winds up being different. But, no, Daisy’s mom could not have been a human. At least not in any way that I can think of.

RH: Right.

PB: Because there was an egg. (laughs)

RH: That [egg] thing totally cuts that out. But why did Daisy not show those dinosaur-like tics as much as the other characters?

PB: I think the argument would be it’s the classic “nature vs. nurture” thing.

RH: Mhm. Yeah.

PB: In Koopa’s world, the dinosaur stuff is cultural. That’s part of the culture. And, yeah, they have aggressive tendencies and they’re lizard-like. I don’t remember how much of our draft got translated, but, when we did our draft, the lizard-world was really kind of a mirror world where everything was turned upside down and everything that could be aggressive and just predatory was highly valued and praised. That was the culture. And expected of everybody. We had roving gangs of kids and of course the cops were corrupt. Everything was supposed to be turned on its head and be this weird mirror world.

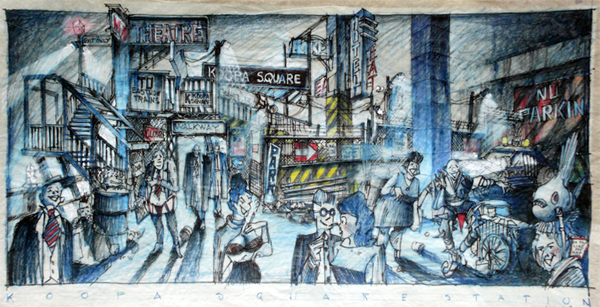

This newly-released Walter Martishius concept art reveals a Koopa Square that jives with Parker and Terry's original script

PB: But Daisy didn’t grow up in that world. She grew up in our world under the care of nuns. (laughs) She may have all those tendencies, but she was nurtured to be a human being. But she understands that she’s different. She knows inside there’s something different about her and she’s obsessed with dinosaurs. There’s something that’s drawing her into that world. It’s a “nature vs. nurture” thing and she was sweet. She was raised to be sweet. Raised by nuns.

SA: Well, there’s a point in your draft where Koopa is telling Daisy about her dinosaur ancestry and repressed reptilian tendencies. She just nods in assent and appears as if she does want to give into her “reptile brain” and carnivorism.

So, I think that was explored a little more in your draft.

PB: Yeah, it could be. I think we also had the sense that Koopa had sort of a hypnotic quality to him. That he could hold sway over people. He might just be a magnetic guy. He was a leader that way. I think that Daisy-and, again, this was a long time ago-I think Daisy’s mother was someone special to Koopa, but she wasn’t human. I think she went and escaped into the other world to get away from Koopa. And I don’t think it’s meant to be implied that Daisy is Koopa’s daughter.

You know, I could be totally wrong here, but I think the idea was “This was someone who was special to Koopa 20 years ago and now Daisy reminds him of that woman and so he has romantic designs on Daisy.” And it doesn’t go well. (laughs)

He is thwarted by Iggy and Spike and he’s thwarted by the Mario Bros. And by the fact that Daisy has no interest to him.

SA: Well, going off the idea of a character really being a dinosaur without outward indication: In your initial pitch it was explained that Mario and Luigi were smuggled into our world from the parallel world by their plumber father, which would imply that, like Daisy, they were also descended from dinosaurs-

PB: (laughs)

SA: Would you say that concept still holds true in the movie?

PB: No. That would be interesting. But, no, I don’t think that ever wound up being considered seriously. Because they have to have too much backstory in our world. That wouldn’t make any sense. The basics of our story [were that] their dad died and left them a plumbing business and if they were smuggled in from the dinosaur world then that couldn’t possibly be [true].

I’m not sure. That doesn’t really ring any bells for me. I’d have to look at [our] pitch again, but I don’t even remember that even being part of our pitch.

SA: Well, the thing is, you wrote the script. Even if it’s not stated outright you could still say “Yeah, that’s true,” just for the cool-factor.

PB: (laughs) The guys have to be human beings because thematically the movie has to be about our base instincts and about how we- You know, Koopa is an object lesson. He’s a guy who’s ransacked his world’s resources and plundered the earth-on his end-for everything it could give him and everything’s a mess and he has no choice but to invade our world. And it’s because he has this reptilian instinct.

I mean, we have a reptile brain. Our base instincts are basically our reptile brain. And so, I think in the backs of our minds the story had to do with “How do we become heroic. How do we rise above our base instincts and just go beyond what we greedily want this second and do what’s right in the long-term.” I think that was in the back of our minds, something we were doing. It didn’t gel in the story, necessarily.

There were a lot of themes floating around. (laughs) I don’t think we nailed down any one of them, which would have made a much better movie. But that was in the background.

RH: One reason we asked the question about the Mario Brothers coming from the parallel world is because that concept was later utilized in the games.

Originally, it was widely accepted that the Marios were plumbers from our world that had found their way into the Mushroom Kingdom. However, Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island, which was released two years after the movie abandoned that concept and stated the Mario Brothers were born and raised in the Mushroom Kingdom from the start. What do you think of that?

PB: I take total credit and expect a check from Nintendo, who will be hearing from my lawyers. No, I think you said it earlier. As games evolved they became more interested in including more story elements, and that’s an interesting reversal. But it’s just coincidence.

"I take total credit and expect a check from Nintendo"

SA: Do you recall any other interesting backstory ideas? Many things just aren’t clear in the story, like why Koopa took over or what kind of a character the king was. Dick and Ian implied in their draft that he was a dictator that was just as bad as Koopa. So, you don’t really know what the world was like at the time.

PB: You would probably know as much as I do on that. We were interested in the backstory to a point, [but] usually we didn’t have it thought out enough to help answer those questions. In our draft King Karma was a good guy and Daisy was his daughter, otherwise she wouldn’t be Princess Daisy. That’s right… It’s all coming back to me now! (laughs)