Interview--Mark Goldblatt (Editor)

Conducted by: Ryan Hoss and Steven Applebaum

October 17, 2010

Mark Goldblatt

Terminator. Predator. Rambo. Planet of the Apes. These are only a few of the franchises that editor Mark Goldblatt has worked on in the film industry. However, what you might not know is that he is on the quite extensive list of incredibly talented people who worked on the Super Mario Bros. film. We had the privilege of speaking to Mark in late 2010 about his experience working on the very first motion picture adapted from a video game. You'll hear his thoughts on the film, why it turned out the way it did, and how--and if--an extended cut of the film is a possibility.

Mark Goldblatt: Okay, gentlemen--good afternoon.

Steven Applebaum: Good afternoon.

Ryan Hoss: Hey. How are you doing?

MG: Good. So, I took a look at your website. Pretty cool.

RH/SA: Thanks.

MG: Lots of information. Boy, you’re really delving in there. It’s really impressive.

RH: It’s as good as we’ve been able to do without actually being there. (laughs)

SA: (laughs)

MG: True. It was a while ago and people forget things. (laughs) You’ve dug up some cool stuff.

So, I watched the movie, which I hadn’t seen in a long time. Aside from the fact that they haven’t done a decent hi-def transfer. It’s letterboxed without 16x9 enhancement, and it’s a little grainy, but I liked the movie a lot. What’s cool about it is that it’s just completely different from anything else, I think.

RH: Well like you said, our big issue is that there isn’t a good enough transfer to really look at and appreciate all the little details that are in the film.

MG: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So, you take what you can get. But it’s amazing. It was made a while ago. 17 years, I guess. Something like that.

We shot it in Wilmington, North Carolina, as you know. I can’t remember how long we were there, but it was a long time. I’m sure Parker [Bennett] told you that. Originally it was meant to be a 12 or 14 week shoot I believe. Whatever it was, Rocky and Annabel’s allotted contractual time to shoot was over, but there was a lot material that we still had to shoot. Plus, on a daily basis, even during the primary shooting period, we discovered that we needed to shoot additional material for the movie to make sense.

So, we were always playing catch-up so that the audience could understand what was going on in the movie. When Rocky and Annabel finished their work we continued shooting with several units. Two to three units, I think, for at least another six weeks or more.

"So, we were always playing catch-up so that the audience could understand what was going on in the movie."

RH: Oh, after they were gone?

MG: Yeah. I mean, you could consider it pick-up shots – stuff that was in the script that we never got to and sometimes even other material to explain plot holes and motivations. In fact, the Lance Henriksen scene at the end of the picture was shot much, much later in Los Angeles.

RH: Yeah. That’s one element of the production that Steven and I have been discussing lately. If they had figured out that cameo earlier they could have possibly shot more scenes with Lance Henriksen during the initial shoot.

MG: It’s conceivable. For example, there could a backstory in which he appeared. There’s a lot of directions that this could have gone in.

RH: Right.

MG: It’s one of those things. I mean, I know that there were many versions of the screenplay. When I was hired I had read the lan la Frenais and Dick Clement screenplay, which I liked very much. It was different. I don’t think it was quite as edgy, as I recall. It was more of a fantasy/adventure. I thought it was quite good. That convinced me to want to do the movie. Plus meeting with Rocky and Annabel, whom I really liked. And I loved Max Headroom, the made-for-TV film they had done. I don’t know if you remember that.

RH: I have, it's excellent.

SA: Yeah, I’ve seen it as well.

MG: For its time it was really revolutionary. So, they were pretty cool. Of course, when I went on-set I met Parker and Terry [Runté]. And somehow Ed Solomon came in; I mean, there [were] all these different writers.

But, it’s funny because Parker and I have remained friends ever since, which is a great thing because I really like him. But–(laughs)–Parker and Terry were the “last men standing” in terms of writers. They were there to fix everything on a day to day basis.

Often after dailies we would have meetings in the editing room between the producers, Louis D’Esposito, the first AD, and Dean Semler – the DP – to try to figure out what we could do to make everything play better, to make it clearer, to make the story better and what shots we were missing. We were constantly creating lists of shots for second unit to play catch-up with.

So, it was pretty interesting. But, if you look at the people who worked on that film there’s some pretty major people. I mean, just start with the producers: Jake Eberts had founded Goldcrest in the UK. He was a very successful financier and had produced many pictures. [He] especially had a long-standing relationship with Robert Redford. He was an executive producer on Dances with Wolves and had a long professional relationship with Roland Joffé. Together, they produced Super Mario Bros.

Morton and Jankel's Max Headroom and Clement and la Frenais' SMB script attracted many people to the project, including Fiona Shaw

MG: These are very educated, very cultured film people. Jake was incredibly well-read, very cultured and had a great sense of story as well as culture and history. Roland was a pretty hot director having made The Killing Fields, The Mission, and City of Joy, among others. Very smart, very well-versed in literature, art, art history, and politics.

At first glance, it seemed pretty unique that these guys were doing the Super Mario Bros. movie. Producing it, in a very creative sense. Not a traditional Hollywood marriage by any stretch of the imagination. Jake had spent a lot of time in Europe. He was very European in his outlook. Roland, of course, is English and had done a lot of theatre, Shakespeare. Stuff like that.

So, you already had a more cultured sensibility going in, for a filmization of a video game. If you look at the actors that wound up in the movie: Bob Hoskins, who’s a pretty great actor. Fiona Shaw, who is an esteemed English stage-actress. More “out of the box” choices like John Leguizamo and Richard Edson, etc. I think all of this and the whole evolution of this project just got it to a place – for better or worse – that was really different from everything else.

Perhaps it was ahead of its time. When people first saw it in the theaters maybe it wasn’t what they were expecting. Maybe it was too much of an assault? I don’t know. It wasn’t a huge hit when it opened. It’s developed a cult following later. Maybe it was just too intense. What do you think?

RH: I think a lot of factors contributed to the failure of the film during its theatrical run, but a big reason is that it wasn’t marketed that well. I believe that the film just doesn’t know whether it wants to be a comedy or an action movie or serious or funny and that was reflected in its marketing. Even though it was revolutionary and interesting it just kind of missed the target audience.

I also think Jurassic Park coming out a week or so later didn't help.

MG: Oh, wow. That’s a very good point. Never thought of that.

RH: I don’t think people knew what the filmmakers were trying to do with the property. It’s taken until now for it to gain enough popularity to develop a cult following. That’s why our site is here. People are starting to realize “Wow. They really were trying to do something interesting and creative with it.” That’s what has made it so incredibly intriguing to us.

MG: Yeah. It’s got an energy and it’s just otherworldly. It really does seem to take place in a parallel universe. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the art direction and production design. David Snyder’s amazing sets and the vastness of converting that cement factory into another world--it really is pretty amazing.

So, as I said before, the quality of all the key personnel on this movie really shows. I mean, Dean Semler – who had done the Mad Max pictures [and Dances with Wolves] – [was the Director of Photography]. Alan Silvestri’s score really powers it. I really liked it. The casting was unique and interesting. Mali Finn [the casting director], who had done Terminator 2, for example, and True Lies did this. [It was] just interesting choices across the board. Top people.

RH: I think Parker said it best when we interviewed him that there were no better people to make this project work than out of all the cast and crew they had. Unfortunately, there were a lot of factors as to why it didn’t work right out of the gate.

MG: Sometimes its difficult to analyze when something doesn’t work or doesn’t sell or people don’t go see it. The short-term, is “Well, it went over their heads.” Were there too many ideas? Was the film trying to be too many things (comedy, fantasy, action film, etc.)?

Well, this was high concept. It was “Super Mario Bros. from the video game in a movie!” “Okay? Now what’s it about and what’s happening?” It’s kind of layered. You don’t just watch it; you gotta kind of work with it.

Mario and Luigi are very positive in this picture. Both of them are in love, and Mario – as the older brother – has a great respect for the tradition of plumbing, which is his life and his work – his work and his life are intertwined. It’s almost a religious thing. He uses his plumbing skills and his passion to get them out of all these jams when they cross over into the [other] dimension.

"[Super Mario Bros. is] kind of layered. You don't just watch it; you gotta kind of work with it."

Luigi seems to have faith in “the unknown,” some “mystical power.” That’s kind of a positive thing, too, because a lot of religions are basically “Have faith in God. God will get you there.” Whatever it is. In a strange way he realizes that faith is what it’s really about. He’s been watching a paranormal “reality show” – and he learns about the possibilities for greater things existing outside of our realm of reality, which is a great parallel for the alternate universe.

I guess – instinctually – when he sees that the Fungus is interceding for them and trying to help them get the girls out and ultimately to use them to get rid of Koopa, [he develops a religious awe and begins saying] “Trust the Fungus. Trust the Fungus” It’s not a “God” thing, but it’s got to do with the spirit and life-energy. The Old King is still alive, just reduced to fungus.

Sometimes I think audiences see something that’s totally “out there” that they’ve never seen before and sometimes it works for them, but very often it just does not compute. Maybe that’s what happened. Too much input. Like I said, ahead of its time. It took a lot of chances. Over time, it is probably more appreciated than it was upon first release.

RH: I’ve said this in other interviews, but – no matter what the filmmakers did – it was going to be a risk because it was the first film ever based on a video game. It was going to be different and it was going to have to change things conventionally.

MG: Sure. It’s just a different thing. But, what can I say? It’s still out there and people are still watching. Maybe more people are watching. The other thing – obviously – this was an independent production made by Jake and Roland, essentially. The companies were Allied Filmmakers – which was Jake’s company – and Lightmotive – which was Roland’s – with some additional funding from some other people. I think Cinergi may have had some involvement.

It was an independent production that became a pick-up for Disney, but not under their Disney brand. When you think about it, this was about as far from a Disney film as I can think that would hopefully appeal to all age levels and hopefully appeal to children. But mainly that’s another thing: maybe it was too out there to appeal to young children.

I don’t know. I never saw any tests on it. We had one preview screening with finished visual effects and sound. It wasn’t traditionally tested to get preview responses, mainly because the visual effects weren’t ready and when they were ready the picture was pretty much done. So, we couldn’t nip-and-tuck and make a few changes.

SA: I do want to agree with Ryan that marketing was the foremost reason why the film didn’t do so well. It’s just surprising considering how recognizable the franchise was, even then. You would expect people to go see it, but it ended up only making $21 million domestically.

That totally surprises me because, even today, you get movies that are adapted from video games, cartoons – what-have-you – and people expect them to be bad, but they still go to see them. While there is a drop a drop-off period for the movies, there really wasn’t one for Super Mario Bros. For some reason it seems as if people just didn’t go at all, which I feel indicates they simply didn’t realize it was out there.

MG: Yeah. It’s a tough one. It’s heart-breaking.

SA: I think all you can really pin it down to is competition from Jurassic Park coming out a week later.

MG: That’s a big deal. Plus what Jurassic did with dinosaurs. It was a different way to do it, but it was kind of revolutionary. CG dinosaurs of that nature.

But, you know, it’s hard to pinpoint what it is. Maybe because a lot of the actors – who are excellent actors – were not movie stars, per say. There was nothing to really hinge it on [or] hooks for an audience to say “Oh, I gotta see that because of this.”

I mean, it had great actors in it. Fisher Stevens and Richard Edson are hilarious as Iggy and Spike. But, at that point they were pretty much “indie” actors. Fisher Stevens was a little more mainstream than Edson, but John Leguizamo was just breaking as a comedian/comic/monologist/whatever. There were no stars, really.

Bob Hoskins was a great English actor, but mostly films that we would consider art films, except of course for Roger Rabbit. You could consider this an art film, if you like. (laughs)

It’s all water-under-the-bridge now.

SA: Well, I think a good way to really start this interview is going back to how you said that the directors and other people had to get together and shoot additional scenes just to make sense of the movie. Back in 2002 at the San Sebastian Film Festival, Bob Hoskins was asked about the movie and he said that after they had spent $10 million Rocky and Annabel were thrown off the project. You then came down and said that you didn’t know what you were going to do because there wasn’t a single finished scene and that everyone basically had a week or two to cobble together a movie and make something as interesting as you could. How accurate of an assessment do you feel that was? How much really wasn’t done?

MG: I do remember that we were concerned. It was a very ambitious project and – in deference to Rocky and Annabel – they didn’t have a heck of a lot of time to shoot. The schedule was set up in a way to make it in a precise number of days, but it became much more complicated with all of these pyrotechnics and mechanical effects and makeup effects and all this kind of stuff.

The schedule has to be totally planned so that you know precisely what you need to get, because you’re constantly at war with the unknown. Like, “Oh my God. The de-evolution machine doesn’t work! It’s not working!” or “The makeup is taking twice as long to get on! The Goomba’s not ready!” or whatever the hell it is. There was lot was going on.

This was compounded also by the fact that there were new script changes coming in all the time because they kept tweaking scenes. I think this would be hard for any director to kind of deal with, but on the other hand some people are fast on their feet or some people clear up all of these issues prior to shooting. We were faced with many challenges.

It’s interesting to hear what Bob Hoskins had to say because I had never heard that.

SA: He said one or two.

MG: Well, I’ll put it this way: politically, there were some issues. I flew to location on the first day of shooting and then I came on the set on day two in the morning and met everybody. A particular executive came up to me and introduced himself. After a little small talk he said “Mark, I won’t beat about the bush; I think we’re in trouble.”

It had to do with that person’s interpretation of the sensibility in which the first day’s scene – a restaurant scene – had been shot. It’s easy to get lost in shooting a scene unless you are very well prepared. Again, a director has to have a precise point-of-view and if you have a creative producer they might have an opposing point-of-view.

"Mark, I won't beat about the bush; I think we're in trouble."

MG: In this scene, Daisy has met [Luigi] and she’s invited to dinner with Mario and Daniella. What you saw [in the theatrical cut] was actually a reshoot of that scene. I’m trying to remember if it was rewritten as well. It might have been. But the first day – I think it was the first day – they did shoot this very different scene in which the focus almost seemed to be more about the foreground and background action and less about what was going on at the table.

I remember one of the issues that we always had were transitions. A lot of the transitions are very rough. You cut out of one scene and [you] cut into another. In hindsight I kept thinking “Why didn’t we come up with some transitional device” like whip-pans or an explosion with a giant ‘M’ coming towards the screen; that sort of thing. Of course, it’s a “band-aid” solution and can wear out its welcome very quickly.

But, as it is, sometimes things just abruptly shift and we tried to use sound to also make that work. Yeah, there were definitely issues. It’s just like “How does this all connect?” It’s funny, because when I watched the movie today – I followed the story very well, which is a miracle because I know when we were doing the picture there were definitely story problems.

What we were constantly trying to do was clarify the story and keep it moving, keep it driving. An example would be when Luigi is talking about the Fungus. You may have a medium-wide shot where he’s talking to Mario about the Fungus and there’s this fungus all around [him] and he’s saying “Look, look! It’s trying to tell us something!” and what was missing was the close-up of the piece of fungus coming down or the little mushroom.

So, it’s like well, we have to see it. We have to see it to ‘get it’! Or [during] the car chase, I remember when we got the initial dailies it didn’t make any sense at all, so we had to figure out “What do we need? We need a close-up of Mario here… We need a close-up of Luigi here… Okay, we got to make sure we know where they’re going.” Stuff like that.

I remember for the car chase we had these little toy cars and we’d get the stunt coordinator in and get the first AD, who had to make everything happen physically on the set. His name was Louis D’Esposito and he is now one of the top guys at Marvel, which is good–(laughs)–because he’s a really smart guy. He was very smart in those days and really helped keep everything together, which is often true for editors, but this was a daily challenge.

It was constant damage control, that’s what it was and trying to keep a sense of objectivity as we looked at what material we had and we cut it together to really be objective and say “Well, do I understand what the point of this scene is? Is there a punch-line? Do I know where the scene is going? Do I know what the stakes are?” That kind of thing. A lot of it really had to do with details. Sometimes there were close-ups or explanatory dialogue that didn’t exist.

But, it was challenging, I’ll tell you that. Luckily I was in the company of some really smart people. (laughs) It could have been a total mess, and I don’t think it is. I think it’s pretty cohesive. In fact, the rough transitions almost work because – I don’t mean this in a bad way – there’s a certain kind of a rough quality to the picture. Rough meaning it’s not sugar-coated. When you think of a kid’s movie or maybe a movie that might appeal to children in an alternate reality you might think that it’s sugar-coated like an old, classic Disney picture.

"It could have been a total mess, and I don't think it is. I think it's pretty cohesive."

MG: But this one, when there’s real terror [and] when there’s real horrible things that could happen [and] when there’s lizards sticking their tongue in your face it’s kind of rough. I can see maybe little kids got a little taken aback, maybe. (laughs) I don’t know, but I like all of that. I think that’s really cool and there’s something about the lizard world – the dino world – that’s creepy. Like, eating those little creatures on a bun. You see that and it’s like “Ugh!” There’s something discomforting about it, which is good, because the whole point is it’s not supposed to be comfortable. I dig it. I don’t know if I answered your question.

SA: You answered it pretty well.

MG: Okay, cool. What else? There must be something...Goombas. I loved the Goombas. We all loved the Goombas. Toad, he’s cool. Mojo Nixon was fun.

RH: Yeah, he was hilarious. We were able to talk to him a little while ago. He had some really funny stories.

MG: What’s he doing? He’s still playing music, right?

RH: I think so. I believe he has a radio show on Sirius Satellite Radio.

MG: Really? Cool. I’ll have to check that out.

RH: Yeah. I think it's called The Loon in the Afternoon.

MG: (laughs) That’s funny. Yeah, Fisher Stevens is producing now. Documentaries. Samantha Mathis is still doing fine work. I get the feeling that the actors – because of all the tribulations that we were going through and trying to keep it on track and everything – in some cases they might not have been so happy about making the movie. (laughs) They used to get together and commiserate.

RH: Well, we heard the story from Parker about how they had to cut some of Dennis Hopper's lines, which made him force Parker to look up the word “act” in the dictionary.

MG: [Dennis] was an interesting character. I remember I needed a close up with specific dialogue of him explaining the de-evolution process to make the scene play – there was just no other way to do it – and he really didn’t want to hear from me, but I was stubborn and adamant and I think because I really respected him as a director and in fact had really liked some of his later somewhat obscure films, he finally relented.

As I was talking to him about why we needed to do this shot, he finally gave in, which was good. Until he could be convinced that this new shot was justified, he didn’t want to know. You had to work with him. He’s not just going to do it blindly.

So, that was interesting. I also remember that at one time – and this has nothing to do with anything except that I thought it was cool – the producers, Jake and Roland, had the actors over on a Sunday night or something to do a Shakespearian reading in their living room. I don’t remember what the play was. But, it was great fun just because they’re all really great actors and they all loved Shakespeare.

I remember Bob Hoskins had brought a very rare bottle of single-malt whiskey that some friend of his had spirited into the United States. I don’t know if you’ve ever had single-malt whiskey, but there’s all different kinds. This was maybe one of the best and very, very expensive. You couldn’t get it in a store in the U.S. Whatever it was, it was pretty amazing.

So – between the Shakespeare and the Scotch – that was nice.

But, in a weird way, when you get people of this level of culture and intelligence making a movie like this you’re going to get a lot of interesting subtext and ideas floating around that’s really above the norm; stuff that the audience might not even get, but it just, ultimately, creates something different and greater than it would be if it [didn’t have] this level of thought behind it. But it was really a group effort. That’s the thing. I must say, with all the disparate personalities: we actually did work very well together. For better or worse, as I say, because obviously the picture didn’t make its money, this was the result.

RH: You said you came in to work on the picture around the second day of shooting. What were your duties around that point? Did you start cutting scenes right after they were shot?

MG: What usually happens is that a scene is shot and then the raw dailies arrive the next morning. In those days we were cutting on film, so it would come in the next day and then the assistants would synch it up. I would look at it and relay any important details to the directors, producers, camera dept. etc.

We used to go to the old Dino De Laurentiis Studios in Wilmington and project the footage at the end of the day.

Then, I would then have all the footage broken down – which is to say each shot – and I would start cutting. So, you try to cut it as close to the shooting day as possible so that we all know if the scene is working. “Are we missing something?” “Did we forget to shoot Daisy’s close-up here where we need a reaction shot from her?” You know, “Does it flow? “Does it work?” “Is it funny if it’s supposed to be funny?” “Do we understand the story point that is supposed to happen?”

So, that’s what you do. You just keep editing. They call it “keeping up to camera." Usually you’re a few days behind, but hopefully not a lot more. That way you can assess what you’re missing. That’s exactly what we did and it turned out we were missing a lot. (laughs)

RH/SA: (laughs)

MG: But, you know: at least it wasn’t a situation where it was too late to shoot it. Luckily, the huge city sets and everything were free-standing. We weren’t breaking them down. I also have to say that things definitely got out of hand. Like I said, we had at least three units shooting.

There was a second unit out shooting and there would be lists of stuff that we needed and sometimes – I swear to god – they would shoot – I can’t remember what it was, though, but it had something to do with freezing pipes and Mario makes the pipes freeze so they can freeze everyone out – additional stuff of guys in freezing rooms and all related to material that we had already thrown out of the movie.

So, they were shooting additional material for scenes that were not even in the movie anymore because somehow there was a disconnect, because all these shot-lists would get issued. We didn’t know they were going to shoot it. [They’d] say “Let’s go over there and shoot this!” (laughs) “No, guys! We don’t need that!” I mean, that happened a couple of times. Mostly though , the additional shooting went pretty smoothly. There would be these cool scenes like when they’re travelling on the Goomba mattress down the shaft in the cold. That’s really cool stuff. That happened much later.

And the Bob-Omb crossing the street. That, also, was a later thing because I think, originally, they didn’t have all that coverage of the Bob-Omb walking across the street and the idea of intercutting it came up. I like that stuff. It worked really well. I remember we had a lot of trouble with Koopa when Mario knocks him off the top of the [walkway] and he falls into the bucket before he becomes a dinosaur again. It’s like “Well, wait a second...how can that dinosaur fit in the bucket?” (laughs)

"Wait a second...how can that dinosaur fit in the bucket?"

RH: (laughs) Yeah, exactly.

MG: Even getting it into the bucket was tough. If you look at it you’ll see that the trajectory in which he’s flying he would be missing the bucket, so we shot a point-of-view into the bucket to correct the axis so that it actually looks [right]. Boy, I must say it was very educational in terms of problem-solving.

RH: We’ve heard that the scene where Koopa de-evolves into a T. rex was not originally meant to be the climax of the film. Nobody knew what it would eventually be since it was changed at the last minute because they had ran out of time or money.

MG: It’s possible. I don’t remember. As I said, it was a long time ago.

RH: Some of the earlier scripts had Koopa de-evolving into a half-human/half-T. rex creature and Mario fighting him on the Brooklyn Bridge in our world. I told that to David Snyder when I interviewed him a while ago and he started to remember that he was researching the Brooklyn Bridge and that they were going to build part of it.

MG: That sounds familiar.

Interviewer's note: We have since acquired storyboards of this very sequence! Look for our upcoming interview with Production Designer David L. Snyder to see what this scene could have looked like.

RH: But, for whatever reason, that changed.

MG: I guess. It may have changed simply [because] that’s a whole new location or a whole new set of visual effects and that would cost a lot of money. [They may have thought] “Why don’t we just do it on existing sets that we’ve got right here?” That would make sense. I’m sure that had something to do with it because you [have to] realize that by going over-schedule and shooting all this additional footage more money was being spent than had been budgeted.

Really, in a sense, it was like this giant snowball that you couldn’t stop. I mean, it had to be stopped. (laughs) There was a point at which somebody had to say “Stop!” but within a certain framework we got as much material as we could to make it work.

RH: Right.

MG: Oh, here’s an interesting thing that you might not know: remember when I told you that we did the Lance Henriksen stuff later? Well, we did in L.A. I can’t remember [which] studio it was, but Dean Semler wasn’t available because he was back in Australia, so we had László Kovács [come in]. Now, if you remember, this was like one shot.

RH: Yeah, it’s like five seconds.

MG: Yeah. But I think we did a whole bunch of takes and all things considered–(laughs)–it probably took a half a day or a quarter of a day or whatever it was, but we had the great László Kovács [come in]. He did Easy Rider and many, many great films. [He was] there for a day. I thought that was impressive. So, I got to meet László Kovács. (laughs)

Oh, and Lance Henriksen met his future wife that day. She was a beautiful young woman who worked in the art department. I ran into them in Hawaii probably about 15 years ago. If Lance hadn’t been cast in that role or she hadn’t decided to come by on the set to visit then they wouldn’t have gotten married.

SA: I know who you’re talking about because I’ve read that story before, but I believe she was in the makeup department.

MG: She was an artist. You might be right. I do remember that she was an artist, though, and one of the things that she had done was she had painted motorcycles. Just these tremendous designs on motorcycles.

SA/RH: Jane Pollack?

MG: Jane Pollack? Maybe it was. Yeah. That sounds right. Anyhow, she was an artist. That was the point. And of course I knew Lance a little bit having from worked on Terminator with him.

RH: In regards to you that extra second unit stuff that was just being shot and filmed that you didn’t need to use: we had an interview with Mark Miller, who played the Street Vendor, and he told us a story about how they had spent all night or most of the day filming him dropping a piece of food off of his cart and one of the animatronic dinosaur-rats would run up, steal a piece it and then run off. That’s not in the movie, so we do know that quite a bit of interesting stuff was going on.

MG: I don’t remember [that] shot per se, but all that stuff that happens in the street with the food vendors and people running around – they shot all kind of grab-shots – little bits that were to create a montage of weird activity going on in the street – and that was probably one of them.

At some point we probably threw everything in and realized that you can’t have everything, so we kept what we thought were the best ones. Like any other beat, you want it to last long enough to satisfy you, but not long enough to bore you or to [make you say] “Next plot point.”

A lot of stuff like that was shot. A lot of detail stuff. I wish, in hindsight – especially for you gentlemen – that we had all of that stuff in a box somewhere, because it’s probably in a landfill right now. Who the hell knows what happened to it, but all that stuff did exist at one time, like on so many movies. But God knows where it would be right now.

That happens. A lot of movies have lost material that people would kill to see.

RH: Yeah.

SA: Yeah. It just kills us to hear that.

MG: The other guy I want to mention – because I didn’t mention him at all and I really, really respect him – [was] our line producer, Fred Caruso, who worked on The Godfather. He was the production manager on The Godfather. I also think he did Once Upon A Time in America. He was an executive producer or an executive in charge of production or something, but he was really great.

Basically, he did all the hiring of crew people and stunt people and second unit directors. He was just amazing. I was real privileged to work with someone like that.

So, yeah. I have to say, the experience of working on that film – although sometimes difficult and maybe even frustrating – but the caliber of the people involved was just spectacular.

SA: It really was. The creative talents behind the film were just amazing. It’s a shame that we can’t fully appreciate their work with the current theatrical release on DVD. The big hope for us fans and many people out there is that an extended or reworked cut may come out at some point.

I mean, there’s someone on our message board who believes that there’s a 5-hour cut somewhere out there. Ryan and I know that that’s just not possible, but it just goes to show the level of passion people have for the film.

MG: No! No such animal exists. I would know.

SA: It’s still an interesting idea considering the cut footage we do know of. There was a whole living world of characters and places in that footage that could make the film a much different creature.

MG: Well, I think it would all be down to finding that material and I don’t know where you would look. I don’t know what they did with everything. There was a certain point where, basically, I think they just ran out of money. I wouldn’t say “ran out of money,” but they just couldn’t spend any more. They were so over-budget and we finished the dub and got our print and that was it.

Now, I remember Disney, who was releasing the picture, had [us] do a video master. I think it was really on video. It wasn’t even digital, which meant they had to have a video master to make the VHS tapes and to make the laserdiscs, and later the DVD, which I’m sure, is from that same master.

Anyway, I was used to being intimately involved in that process because you can’t just let a video house make those masters. That would be like doing a digital intermediate today and not having the director and DP involved. You can’t do that. Unsupervised technicians have no idea what the movie’s supposed to look like, and they have no investment in imperfections happening within the shot that are fixable during that process. If you catch it you can usually fix it.

That’s the last thing I really did on that movie and I don’t know where the elements are. It’d be interesting if you guys can track it down.

I know there’s a similar situation with Clive Barker. I did a movie with him called Nightbreed and Clive and others have expressed interest over the years to try to find his original director’s cut. But, nobody can seem to locate it.

SA: It’s both confusing and saddening the way that films are so easily discarded. You really don’t know what’s going to happen 20 years down the line. People might start appreciating it and might want to revisit it. That footage could become very valuable.

MG: That’s exactly right. Definitely all that material should be saved.

SA: The same thing happened with Blade Runner: it wasn’t initially well received, but over the years it developed a following and became the classic we all know.

MG: Exactly. Well, luckily they’ve been able to make several versions of that movie. That’s a good thing because they’re all interesting. I love Blade Runner.

It’s funny. I remember seeing Blade Runner with the narration and thinking it was great and then I remember going to a screening here in L.A. at a theater that just closed last year. The Fairfax theater.

They had this 70mm festival – and this was kind of a fleabag multiplex – and I went there and it was packed and it turned out that what they showed was a preview print. You may remember the story when they discovered an older version that was closer to Ridley Scott’s original vision of the movie. It was screened by accident.

RH: Yeah! That was amazing.

MG: This was it. It was like, we were all watching this movie and suddenly [we think] “Wait a second… Where’s the voiceover?” The narration wasn’t there. And then there’s the unicorn. “Wait, that wasn’t in the movie!” And all this other stuff. It was this early preview version and it had a lot of temp music in it and people went crazy.

I remember the production designer...our production designer David Snyder was the art director on that picture, but the production designer of Blade Runner was at that screening and – not realizing how revolutionary it was to see this – he just went ballistic saying “This isn’t the version of the movie that we put out!” (laughs) “I’m going to call Ridley!” (laughs)

His name was Larry Paull. He was a really great guy. I got to work with him on Predator 2. I remember he was just livid. (laughs) And then everyone realized “Well, wait a second… That means that these elements are out there somewhere. Here’s this version,” and then they start looking for everything else. Ultimately, you get this 5-DVD set they put out of every imaginable version of Blade Runner. Maybe they’re not even done yet. Maybe they’ll be another one. Who knows.

All great movies should live on.

RH: Right. Well, since you personally edited Super Mario Bros. can you tell us if there’s a longer cut out there or not?

MG: There was a longer cut. At some point we cut together everything. But in the process of making it, certain material gets edited out. I can’t tell you what those scenes are – you probably know better than me – but, for one thing, the movie would have been too long, and for another thing some of the scenes didn’t work optimally for whatever reasons.

So, there was more stuff. I’m sure there was more stuff with the Brooklyn Girls, for example. But, you know, how many times can you cut to the Brooklyn Girls? You can only cut to them as many times as it serves you in conjunction with Mario and Luigi’s quest to save them.

RH: Right.

MG: Otherwise it becomes about them. So, stuff like that. Especially in those days when you were working on film, because unlike the digital editing that you do now where you can keep different versions in the computer to reference when you’re cutting on film you basically had only one copy of the edited movie. It’s the workprint.

So, my point is that the workprint was the only version of the movie. Unless you’ve previewed it or in those days had to have made a black-and-white dupe so that you can do your temp sound mix. We didn’t have any previews. The only preview we had was with an answer print, because we had already mixed the movie. We were able to make a few minor changes before we cut the negative.

Since there never was a black-and-white dupe made except for the final version, there is no record of a longer cut. The only thing that could exist is if somebody found all of the cutting materials – all of the film – because what we used to do in those days was when you cut whole scenes out of a movie you would keep them. They would be called “lifts.” You know, scenes that we took out of a movie. We would put them in some boxes that would be called “lifts.”

So, if you could ever find that material, then you would somewhere find a box full of lifts. They would be scene-by-scene – not necessarily integrated into the movie – but you’d have all these deleted scenes.

RH: I guess that’s the point where we’re at now, is trying to figure out who actually has it. Disney is the company that now produces the DVDs, but do you think that they would have these materials?

MG: I really don’t know. I mean, you can try Disney. I don’t even know if Disney still has rights to that movie. I have no idea.

Well, they must because they put the DVD out. What was it, five years ago?

RH: The first DVD came out in 2003, but they just re-released it again this year.

MG: But with the same–

RH: Yeah. They just moved some text around on the DVD cover.

MG: Ugh. God.

RH: Yeah...

MG: It’s a really crummy [DVD] picture.

RH: Yeah. We’ve sent countless E-mails to Buena Vista asking for at least a widescreen transfer, but they’re just not listening. (laughs)

MG: No. Well, they’d have to find the elements. They don’t want to blow it up and then squeeze it down again.

RH: Steven, correct me if I’m wrong, but aren’t there several international releases of the film that are anamorphic widescreen?

SA: Yes, there are.

MG: Really? That would make sense, because different elements went off to different countries. I don’t even know if Disney had worldwide release on this picture. They may not have.

RH: I don’t think they did. I think Warner Bros. released the film in Spain.

SA: Another thing is that despite some of these international releases being widescreen or having somewhat better picture quality they also typically have worms and artifacts. They still came out worse in some area. You just can’t win with this movie.

RH: Yeah. (laughs) If you had to guess – since you said that there’s a longer cut – how much longer do you think the original cut was than the released version?

MG: Well, let’s see… The released film was, what, a hundred-and-some odd minutes?

RH: An hour and forty minutes.

MG: An hour and forty; a hundred minutes. I would probably say not more than two hours and ten minutes, maximum. But, I don’t know if we ever played anything that long because for a movie like that even a hundred minutes seems about as long as you’d want it to be. I can’t imagine you’d want it to be longer because it just wouldn’t have any pace to it.

RH: We thought one reason why those scenes were cut was so that the theater could potentially run the film more times in a day.

MG: No, it was so that the film would play more entertainingly and not overstay its welcome.

RH: Since Disney distributed the film do you know if they had any say over the final cut? Did they want anything taken out to get the rating down?

MG: No, no. As I said, when we previewed the picture – and that was pretty much the first time Disney saw it – it was done. I think we went back and made a few little trims, [but] not much. I don’t recall any notes [from Disney]. There may have been one or two notes, but they were minor.

I think maybe we went back into the mix and took everything down a little bit because it was probably a little louder when we screened it, but that’s about it. I don’t recall any notes from Disney.

RH: Cool. I ask because one of the scenes we’ve researched is when Fisher Stevens and Richard Edson's characters, Iggy and Spike, rap in the Boom Boom Bar.

MG: Oh, there was a rap song. There was. I definitely remember that. It could have been in the preview and, basically, it was fun and I think they were singing about Koopa, but in the interests of not stopping the movie for a song and dance number, we trimmed it to keep the story flowing. That’s part of the editing process.

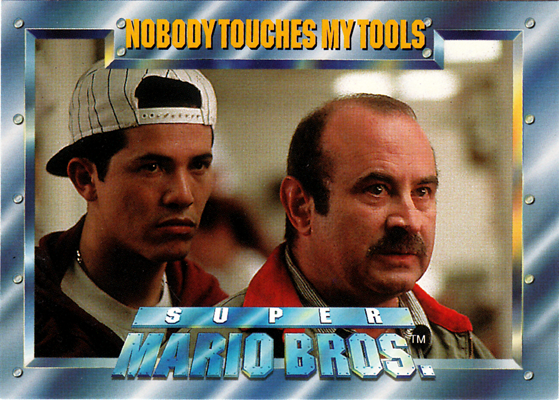

Photo courtesy of MEL

The ever-infamous Spike & Iggy Rap scene

SA: That makes sense, though Ryan and I have speculated that it might have been cut to bring the rating down. We’ve seen in promotional photos that there were several scantily-clad women dancing around them as they sang. Do you think that might have been a factor as well?

MG: It’s possible, but I’m sure there are also scantily-dressed people in that scene anyway.

SA: You can see them for a few seconds in the background of the scene, but they’re not in the forefront as much as they were in that one cut sequence.

MG: I see, yeah. Well, that could be. I don’t think that would have been a censorship thing, that would have been a sensibility thing. I always like it when people break out into song in a movie. Of course – here – they were in a club, so it was more natural to do.

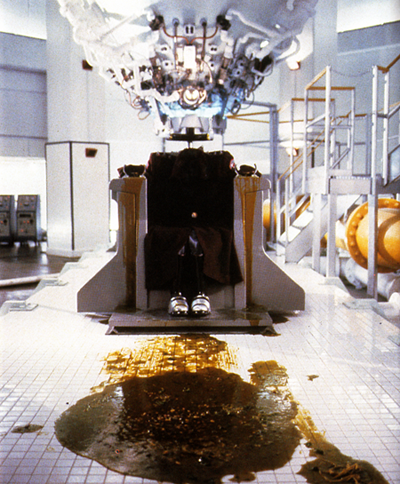

RH: I suppose the most important and contested deleted scene would have to be the extended de-evolution chamber sequence. On our Deleted Scenes page you can see that we have about as much information on it as we can muster.

MG: The de-evolution scene and who gets de-evolved? I remember there were a bunch of characters. In fact, I remember people being de-evolved into slime that aren’t in the movie anymore. One of the cops?

RH: Well, we don’t know who exactly it was other than Toad that was de-evolved. On our Deleted Scenes page we have a VFX shot that depicts what looks like one of the de-evolution technicians getting de-evolved into slime.

MG: That’s right, that’s right. I remember Annabel used to say about that guy “He’s got a face that was born to be slimed.”

RH/SA: (laughs)

RH: So, what was going on with that scene? It seems like they just couldn’t make up their mind who should be de-evolved.

MG: I don’t remember. It was just a throwaway. It was like “This is what Koppa does to his minions when they mess up.” We figured we had enough of those moments. Of course, Iggy and Spike get evolved as opposed to devolved.

For some reason I remember an image – but maybe I imagined it – of Toad being re-evolved, but maybe I’m wrong.

RH: Ohh! Really? (laughs)

MG: Maybe I made that up. Maybe I’d like to have seen that.

RH: Yeah, I think we all wanted to see that, but it would be interesting if that actually happened.

MG: Could have been. Could have been.

SA: Ryan has this image of an ideal ending in which Toad is re-evolved, the King returns and Mario and Luigi are thanked in just this huge “knighting” ceremony.

MG: Wasn’t that in an earlier draft of the script?

SA: Toad is never de-evolved at all in some of the earlier versions of the script.

MG: Ah. Well, okay. There you go. I always found it sad that Toad got de-evolved. I liked Toad. He’s a cool cat.

SA: Toad actually remained alongside Mario and Luigi in earlier scripts, helping them throughout the adventure. The Goomba that Toad would become was a completely separate character named Hark.

MG: Right. I don’t know. I might have made it up, but it feels right. (laughs) I would have liked to have seen it.

RH: Well, was that sequence when the technician is de-evolved finished?

MG: Yeah, it was in the movie at some point, but it was just a little throwaway [sequence]. It was like “You screwed up and we’re going to slime you.”

RH: The confusing part is when you watch the movie there’s suddenly this big pile of green goo on the floor after Toad is removed from the de-evolution machine. It’s like “Where did that come from?”

MG: Well, that’s obviously the guy who got gooed. So, you’re right. Good eye.

Honestly, I don’t remember the evolution of why these things were taken out or not, whether I decided to do it or whether somebody else thought it was a good idea. But, you know, we were trying to get the picture down to a playable length.

"Well, that's obviously the guy who got gooed."

RH: Right. That would make sense.

MG: But it’s true, because there’s something about getting the concept of slime as a de-evolution end-result, that also would have given us better understanding of what happens to Koopa at the end. When he gets, basically, turned into primordial ooze.

RH: Now, getting back to the beginning of the film, there was an extended sequence featuring Koopa chasing down Daisy’s mother while in the rain. Do you remember how much of that there actually was?

MG: I can’t remember, but I think that scene was always in the script and always in the picture.

RH: Yeah, it was.

MG: Koopa may have had a few more lines when he appears there. But that’s a nice little scene.

SA: Yeah. It’s really unfortunate that that scene was cut down because it’s one of our favorite scenes in the entire film. It’s just brilliantly shot with the whole atmosphere and the music. There’s just a good mood to it that sets the movie off on the right tone. Unfortunately, they put that animated intro right before it.

MG: Yeah, the animated intro… They did that basically just to give everyone a little set-up. They were worried that people didn’t get the connection between dinosaurs and Koopa and all those people who appears human, but who really had come from the dinosaurs and all that stuff.

But, totally, that introduction is just very different from everything else. And, you know, of course that the [narrator was] Dan Castellaneta.

RH: The other thing that comes to mind is – and this might be self-explanatory as to why it was cut– the whole subplot with Mario and Luigi’s rivalry with the Scapelli plumbers, Mike and Doug.

MG: Yeah, yeah. There was more. I can’t remember what, but there was an ongoing feud between the Mario Bros. and the Scapellis. It was only alluded to [in the completed film].

RH: How much of that was shot? It seems like there was a full scene or two with the Scapelli plumbers.

MG: Yeah. I honestly don’t remember, but I seem to remember that there was some kind of phone call between Scapelli and Mario.

SA: With those scenes you would expect that conflict to be resolved at a later point, so what I’m wondering is whether the Scapelli Bros. returned at the end of the film?

MG: It just sets up the conflict a little better because, right now, you don’t really get the fact that the Scapellis are in competition and are playing “dirty pool” with Mario. You get it because Mario tells us that. “The Scapellis again!”

So, that’s all you get. Although, you do see the Scapellis [flooding the tunnels later].

RH: Were the plumbers that caused the flooding in the tunnels meant to be Mike and Doug, or just generic “Scapelli plumbers”?

MG: I don’t know. I couldn’t tell you. It might have been.

So, you kind of get it there. Maybe that’s what it is. The other Scapelli scene would have been a redundant scene. The script changed throughout the shooting and the movie changed because certain scenes were taken out and certain scenes were kept and certain scenes were rewritten or whatever, so that’s why something could have been shot with the intention of selling a certain animosity between the Scapellis and the Marios and then you realize you have enough of that in the movie. You don’t need more.

RH: At the end of the film Scapelli himself is de-evolved into a chimp, but in one of the earlier drafts they do bring Mike and Doug back and they get de-evolved into chimps instead.

MG: That I don’t remember, but I don’t think they shot that.

SA: This is more general, but – having watched the film recently – did you notice any sections where a shot or even a full scene might have been cut?

MG: Well, yeah. We know that there have been scenes that were cut, but I don’t think there’s that many. I mean, you mentioned one that I had totally forgotten about.

I think there was more stuff with the Brooklyn Girls. There was at least one other scene in their barracks, maybe two. I think there was more stuff with Toad in jail.

RH: Yeah! We heard from Mark Miller, who played the Street Vendor, that he was also a dino-human (“Lizard Man”) in a cell right next to the Mario Bros. during the jail scene. He said that they filmed a shot of him smoking a cigarette and flicking it at them.

MG: That’s right. Flicking the hot ash.

RH: Right. Was that just a little shot or was there more to it?

MG: It was a short “scene-lette.” But, we took that out.

RH: One thing that we’re really trying to figure out is how much of this was shot and how much wasn’t. It seems like there’s a completely different introduction to the film in how the Mario Bros. meet Daisy. The scripts and several promotional photos depict the Mario Bros. in a restaurant eating and that’s where they meet Daisy, rather than outside at the payphone.

MG: You know, I think that might be right. Remember I told you that one of the first scenes was a restaurant scene. That might have been it.

RH: Yeah. It seems like it was rewritten so that they could have Mario and Luigi meet Daisy sooner.

MG: It’s possible.

I think there was more stuff at the Mario apartment, but I can’t tell you what. I think there was more stuff at Daisy’s base camp, when they’re doing the excavation.

RH: Oh really?

MG: I think there was a little more stuff there, but it was all expository.

RH: When you mentioned the Mario Bros. apartment I’m reminded by the early scripts depicting Mario and Luigi getting ready for their date with Daniella and Daisy.

MG: Yes! That’s right. They’re getting dressed or whatever they are and they’re looking in the mirror.

RH: Right. And Luigi’s listening to Red Hot Chili Peppers while Mario is listening to Frank Sinatra, or something like that.

MG: Yes. That was shot.

RH: And that was shot? Wow.

RH: That would have been cool. (laughs)

SA: Yeah. (laughs)

MG: Yeah, it’s nice. But, you know, if all that stuff had gone in the movie would have been over 2 hours, and it would have dragged.

RH: Of course.

SA: One strange thing I’ve noticed during the climax is when we see Koopa chasing Mario through the streets, which cuts to the meteorite chamber with Luigi and Daisy, only to cut back to Koopa and Mario suddenly having a standoff on the galley-way. It’s like, “Well, how did they get up there?” I’m wondering if there was an extended chase scene to explain that.

MG: Well, there was more stuff there during their confrontation. I know that. When they’re walking towards each other [and] all that stuff. There was more stuff. I don’t remember if we covered Mario getting up to the top or not.

Just like you, I would have to see that footage, then it would all come back to me. But even from what you guys have been saying to me I’ve been remembering some stuff. The Mario apartment scene [and] things like that.

RH: Were there any scenes that were cut because the effects weren’t finished in time?

MG: I don’t think so. I can’t think of anything like that.

RH: Okay.

MG: Did you ever speak to any of the visual effects people?

RH: Actually, I have an interview scheduled with Chris Woods.

MG: Good. I was going to suggest that you talk to him. I’m sure he’ll have some interesting things to say.

RH: Maybe this is something you can expand on, but sometimes when you watch the film – and I suppose this happens with a lot of movies – the frames are inverted.

MG: A flop shot? Is that what you mean?

RH: Yeah. I’ve noticed a few, like when the Mario Bros. escape from the police station and when they’re in the police car. I believe it’s flipped and you can actually read that “POLICE” is inverted.

MG: That’s probably right. We do that a lot. With CGI you can change that POLICE thing and flip it back, but – yeah – you have to do that sometimes because sometimes the screen direction is wrong. If everything’s going left-to-right and then suddenly you’ve got a shot and it’s right-to-left and you don’t have something to cut between them, it won’t work.

RH: That makes sense, because when I watch that scene the Mario Bros. turn out of the police station towards the left and because the next shot was flipped it flows well.

MG: Alright. I think we’ve covered a lot of ground. So, E-mail if you have any other questions that I can easily answer, but I think you pretty much tapped me out in terms of what I can remember.

RH/SA: (laughs)

MG: So, cool.

SA: Well, thanks a lot.

MG: Sure. My pleasure. Let me know if any of this stuff comes out on your website and I’ll tune-in.

RH: That’ll be great.

MG: Alright, gentlemen. Well, thanks. Have a good Sunday, or whatever’s left of it.

RH: Definitely. Thanks a lot, Mark!