Eight Bits Against Eight Colors: Super Mario Bros., Dick Tracy and the Almost Unreal

Written by: Adam Bertocci

Posted: June 22, 2019

Super Mario Bros. (1993) and Dick Tracy (1990)

Among the myriad criticisms of 1993’s ill-fated Super Mario Bros. movie, the easiest—if indeed it’s a criticism at all—is that ‘it wasn’t like the games’. Fans of the film, myself included, prefer to frame its departure from the source material as a positive, praising its creativity, which somehow always comes off as a backhanded compliment.

It is, of course, true that the film hardly captures the bright, bouncy vision of Nintendo, eschewing blue skies and fairy-tale castles for an urban dystopia closer to Blade Runner than World 1-1. With earthier characters replacing the cheerful cartoons and a plot so complex that documenting it clearly onscreen legendarily evaded its own directors, the movie is its own beast, for better or worse.

If indeed the film’s error was diverging from the games, then what, perhaps, the world wanted was something like Dick Tracy.

1990’s Dick Tracy must, as the cliché goes, be seen to be believed. Warren Beatty’s film enthusiastically replicates the bright, bold colors and bizarre designs of Chester Gould’s creation. In the comics, Tracy wears a yellow hat and coat. Any other movie would have shrugged and dressed its detective in traditional trenchcoat beige, for realism’s sake. This one puts him in literal yellow and demands that you accept it. Indeed, everything in the movie comes down to one of eight Sunday-strip colors. (Really, six, plus black and white.)

Three years later, Super Mario Bros. wouldn’t put its heroes in their signature colors till over an hour in. Poor Luigi doesn’t even get his mustache…

Comparison and contrast seems inevitable.

On certain levels, Super Mario Bros. and Dick Tracy share some DNA. Consider the connections: Disney brand. A classy pedigree from the producers. Big names playing the baddies. Academy-Award-winning cinematographers. Extensive rewrites—including, amusingly, parallel reworkings of female leads from other material strewn about the canon. (Compare Daisy stepping into the “Princess Toadstool” role with Dick Tracy’s Breathless Mahoney re-imagined as both the Blank and a gangster’s moll recalling the lesser-known character Sleet.)

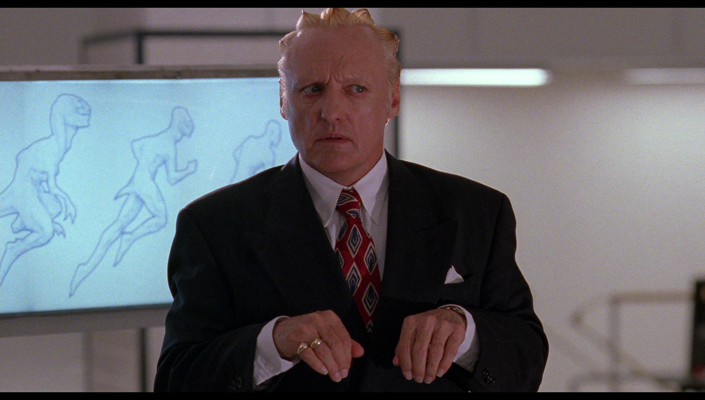

Yet the two films’ similarities are dwarfed by the distance between their aesthetics. Under the direction of Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, Super Mario Bros., eager to deliver on its tagline (“This Ain’t No Game”), turns its back on the storybook look of the games and leans into science fiction, resetting the Mushroom Kingdom to a fungus-plagued parallel dimension of humanoids descended from dinosaurs. Magical concepts from the games become technology: flower-powered fireballs convert to flamethrowers, big jumps between platforms come on assist from spring-loaded shoes and fanciful enemies get categorized as evolutionary half-steps. For the most part, the movie tries to flesh out the fantasy, and even when it doesn’t succeed, it’s still fun to figure out what it’s trying to do. (Dennis Hopper holding his hands like a T-Rex is genuinely inspired, the dreamy waltz “Somewhere, My Love”’s similarity to the NES classic’s underwater score is a subtle treat, and I shamefully admit it took me years to notice how its final battle pays homage to the last fight from Super Mario World.)

Dennis Hopper as "Koopa" in Super Mario Bros., mimicking his reptilian ancestors

While Dick Tracy is set in the past—or a vision thereof—Super Mario Bros.’ Brooklyn scenes are set, as a title card helpfully informs us, “now”, and its dystopian dimension suggests dark times to come—after all, Blade Runner, Dinohattan’s design’s clearest ancestor, took place in the highly-futuristic 2019. The urban nightmare outright makes Luigi suggest that the brothers have arrived in the Manhattan of the future. Past and future similarly inform the respective films’ behind-the-scenes tools and techniques: Dick Tracy is a showcase for handmade matte paintings and traditional in-camera effects, while Super Mario Bros. is an early groundbreaker for computer graphics on film, beating Jurassic Park to the big screen by days.

Dick Tracy lovingly embraces artifice; its lavish environments and meticulously curated colors are no more true to life than the generic red “CHILI” cans that Tracy heats up. It’s an unabashed comic strip, sensationally stylized. Super Mario Bros. seems to go that route at first, beginning with the nostalgic strains of its classic theme and a pixely, animated intro, showing greenery, blue sky, white clouds—then promptly destroys that lush landscape to create its dark dimension. Everything transpiring across the next 65 million years, from good old Brooklyn (even when it’s Wilmington, North Carolina) to a carefully-crafted dinosaur dimension, is meant to fool the eye. Super Mario Bros. doesn’t want you to know that it was filmed in a cement factory. Dick Tracy doesn’t mind if you notice the brushstrokes on its paintings.

In short, where one zigs, the other zags—and then some.

Comparison of the background techniques used in Dick Tracy (top) against Super Mario Bros. (bottom)

In hindsight, perhaps the approaches could have switched.

The Mario games were beloved known quantities in 1993, by one survey’s reckoning more recognizable than Mickey Mouse; every kid knew the look, the feel, the fact that both brothers wore mustaches. Dick Tracy, by contrast, wasn’t something most children knew chapter and verse in 1990; the target audience had no grounds to complain that one key character had somehow gained a mustache in the journey to the screen. Yet every effort was made to market Dick Tracy to kids on the scale of the prior year’s Batman, as if to convince ten-year-olds of their excitement for old favorites like Flattop and Pruneface.

It’s ironic. Dick Tracy could have been anything; the intended demographic had no preconceived expectations, no eye for its audacious visual style and no appreciation of the effort made to replicate Chester Gould’s designs. Super Mario Bros.’ target audience, by contrast, had the games’ iconic imagery burned into its collective retinas and didn’t see much of it on screen.

A Super Mario Bros. movie made by the Dick Tracy playbook would have answered every prayer of the fan dismayed by too much creativity. Green pipes, punchable bricks and floating question blocks, a Koopa named Bowser with horns and red hair, all coaxed into the third dimension in perversely literal fashion. Every location, enemy and power-up that could be shoehorned in would have been. (We will spot the hypothetical filmmakers here the good sense not to cast Madonna as Princess Toadstool.) Based on Dick Tracy’s affectionate preservation of comic-style dollar bills adorned with $ signs, we can even imagine how this movie’s gold coins might appear. The goal would be a family-friendly fantasy that marries the visual style of The Wizard of Oz with the derring-do adventures of, perhaps, Star Wars? Indiana Jones? The Goonies? Is this doing anything for anyone?

Flattop in Dick Tracy (left) vs. Goomba Toad in Super Mario Bros. (right)

One can also imagine a Dick Tracy movie in the Morton-Jankel mold—re-imagining Tracy as a pricklier character, eschewing his retro world and limited color palette for a darker, moodier neo-noir set in an alternate ‘90s of sin, vice and neon. With any luck, critics might stroke their beards and declare it a sophisticated update, as necessary a tonic as the 1989 Batman’s welcome divergence from the infamous “Pow! Whap!” hijinks of the ‘60s TV series.

I think both movies might have worked.

And yet—would they really be better than the movies we got?

I love Dick Tracy as it is. I can name few movies that look or feel like it (the Wachowskis’ underrated Speed Racer took the next logical step, a mere eighteen years later). One full decade before X-Men’s joke mocking Wolverine’s comic-canon yellow spandex, Dick Tracy was dressing its hero the same shade and relishing the prospect.

What would Dick Tracy have looked like, really, unskewed from its comic-strip colors and implausible designs? A gritty noir detective story—hardly untrodden ground—with a few extra scars on people’s faces. The proposal I outline above says a lot about what we’d subtract from the film as it is, but little about what would be gained. It risks the pitfalls of another ‘realistic’ adaptation of 1930s serials and strips—the 2007 TV show Flash Gordon, a muted take on material that didn’t really need one. The famed 1980 Flash Gordon feature film, by contrast, goes the Dick Tracy route, bright and bold and unbelievable in both senses of the word. For its pains, it remains a cult classic—and you gotta love that song.

The 2007 Flash Gordon TV series (left) vs. the 1980 Flash Gordon film (right)

Similarly, Dick Tracy is now best-remembered for, and not in spite of, its excesses and oddities, visual and otherwise. A film that turned away from these touches because something more contemporary, more serious, more real, would have a lot of work to do to make up for what it’d let slip away.

And Super Mario Bros.? What can I say—that weird, weird movie somehow worked its way into my heart starting opening weekend, and refuses to depart.

Both films have their flaws. Super Mario Bros. in particular is fair game for critique. It doesn’t know what kind of movie it wants to be; it’s a kiddie movie sometimes, a weirdo cult comedy at others, part dark sci-fi, part wacky-ass romp, and the disparate elements collide like bumper cars when they ought to resolve into a satisfying whole. It’s someplace between the attempted cross-species seduction, the sentient fungus and the dancing Goombas that one grasps that the filmmakers struggled in balancing a patchwork of competing screenplay drafts. Plot threads never quite congeal, and stray ideas stick out like sore thumbs on reptiles that somehow evolved them.

And yet when I criticize it, it’s not because I want it to be more like the games.

It’s because I wish it did a better job of doing what it wants to do.

(Hell, even Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto thinks maybe the movie was trying too hard to be like the games, a thought I’m not sure I agree with.)

A Super Mario Bros. film that took the literal approach, Dick Tracy’s approach, might look like one I mentioned earlier—Speed Racer. (A film that plays something like an adaptation of Mario Kart.) You can look at that movie’s hyperreal blue skies, blinding deserts and clean lines, imagine a less frantic pace, and perhaps you’re on your way. Indeed, John Goodman’s portly, mustachioed character even dons blue overalls and a red shirt…

Would I like to see that movie? Absolutely.

Would I have liked to see it in 1993?… There’s the problem.

John Goodman as Pops in the Wachowskis' Speed Racer (2008)

Super Mario Bros. in the Speed Racer style for a 1993 release wouldn’t have looked like Speed Racer. In attempting to update the fantastic visions of The Wizard of Oz for the largely pre-digital age, it could have easily failed to live up to the look of, say, 2012’s Oz the Great and Powerful—and come off more like 1978’s The Wiz. The Wiz boasts some nifty matte paintings, but even director Sidney Lumet admits the movie didn’t come together as he’d hoped. (“From large things to small, I felt the concept going out the window,” he writes in his indispensable memoir Making Movies. “I could feel the visual approach leaking out of my hands like water through my fingers. It happens.”) When The Wiz works, it does point the way toward a Mario movie that might have worked, too—the exterior library set has a very classic-Mario look to me, and its yellow brick road coincidentally recalls the ground texture in the NES original—but somehow it all comes off dispiriting rather than charming. What should be magical looks dreary, and instead of endearingly handmade, the world just reads as false.

Say what you will about the Mario movie we have, most of the visuals hold up. It’s hard to imagine a film of its budget doing better with the parade of creatures and diverse environments necessary for a more straightforward take on the games. Dick Tracy had its challenges, but everything it had to depict—ugly men, sprawling cities—was grounded enough in reality to be achieved through existing paint and makeup techniques, with few restrictions to constrain its artists’ talents. A survey of even the most lavish fantasy films of the ‘80s and ‘90s, where one’s options were puppets, animatronics and people in suits, might reveal what a tall order a traditional Mushroom Kingdom would be. (I picture Return to Oz—there’s that Oz thing again—or Labyrinth. Your mileage may vary.) Perhaps the only way to do justice to the Mario catalog of characters, from Chain Chomps to Shyguys to Koopa Paratroopas to Lakitu up on his cloud, would have been to take a cue from another notable Bob Hoskins movie, and draw them as cartoons.

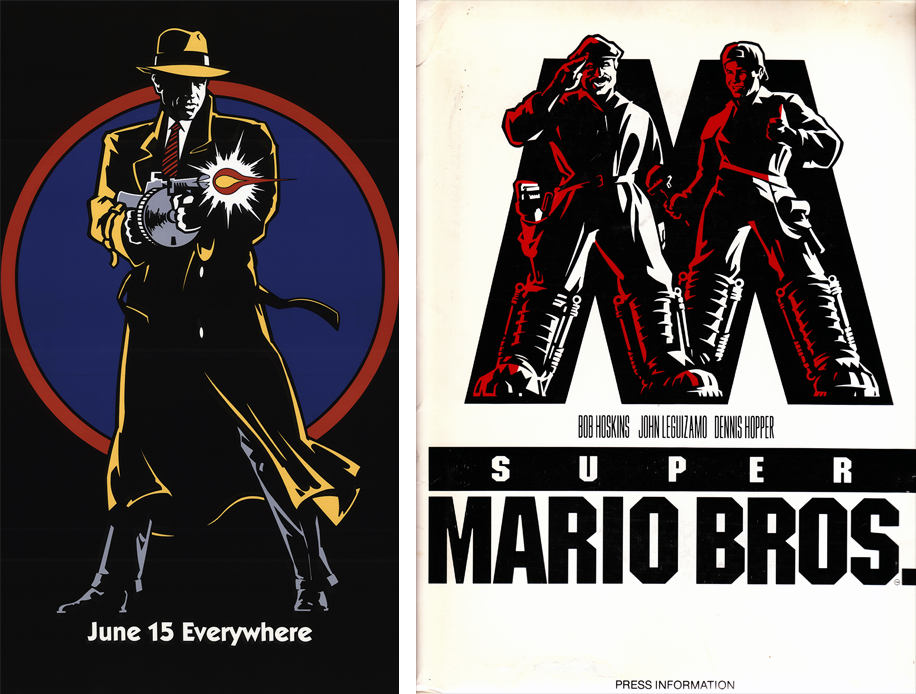

Promotional artwork for both Dick Tracy and Super Mario Bros. used striking, minimalist graphic design elements

Whatever Super Mario Bros. and Dick Tracy’s differences, they share one crucial quality: they aren’t the movie the world might have expected. And therein lies their strength. They’re not aimed at some generic ‘everyone’. They avoid the middle of the road. In Dick Tracy’s case, this audacity led to admiration from critics who got the joke, solid box office performance if perhaps, in the end, some audience befuddlement, and even a little Oscar gold at the end of the eight-color rainbow.

In Super Mario Bros.’ case, it led to… Super Mario Bros.

Yet today, both films are remembered more fondly for the stars they reached for than as the simple summer diversions they were advertised to be. Considering how many pedestrian comic adaptations Hollywood coughs up, it’s only right to honor more ambitious work like Dick Tracy—and the less said about the average video-game-to-forgettable-movie translation, the better.

Super Mario Bros. gets lost in that translation, but the result is fascinating, and, whatever else it is, it's hard to forget. It ain’t, to acknowledge the poster, no game, but it doesn’t quite land in reality, either. Mario sends us off from the film with the words “I believe”: Roxette escorts us home with the chorus, “It’s almost unreal”. It’s somewhere in between those states of mind that movie magic resides.

--Adam Bertocci

Adam Bertocci is a writer, filmmaker and screenwriter working in and around New York, best-known for the surprisingly educational mashup Two Gentlemen of Lebowski, published by Simon & Schuster. He has stolen Mario’s line “She’s nice, go talk to her” for more projects than he cares to admit. Visit him on the Web at www.adambertocci.com.